Coronavirus treatment’s surprise approval gets a mixed reaction: Here’s why

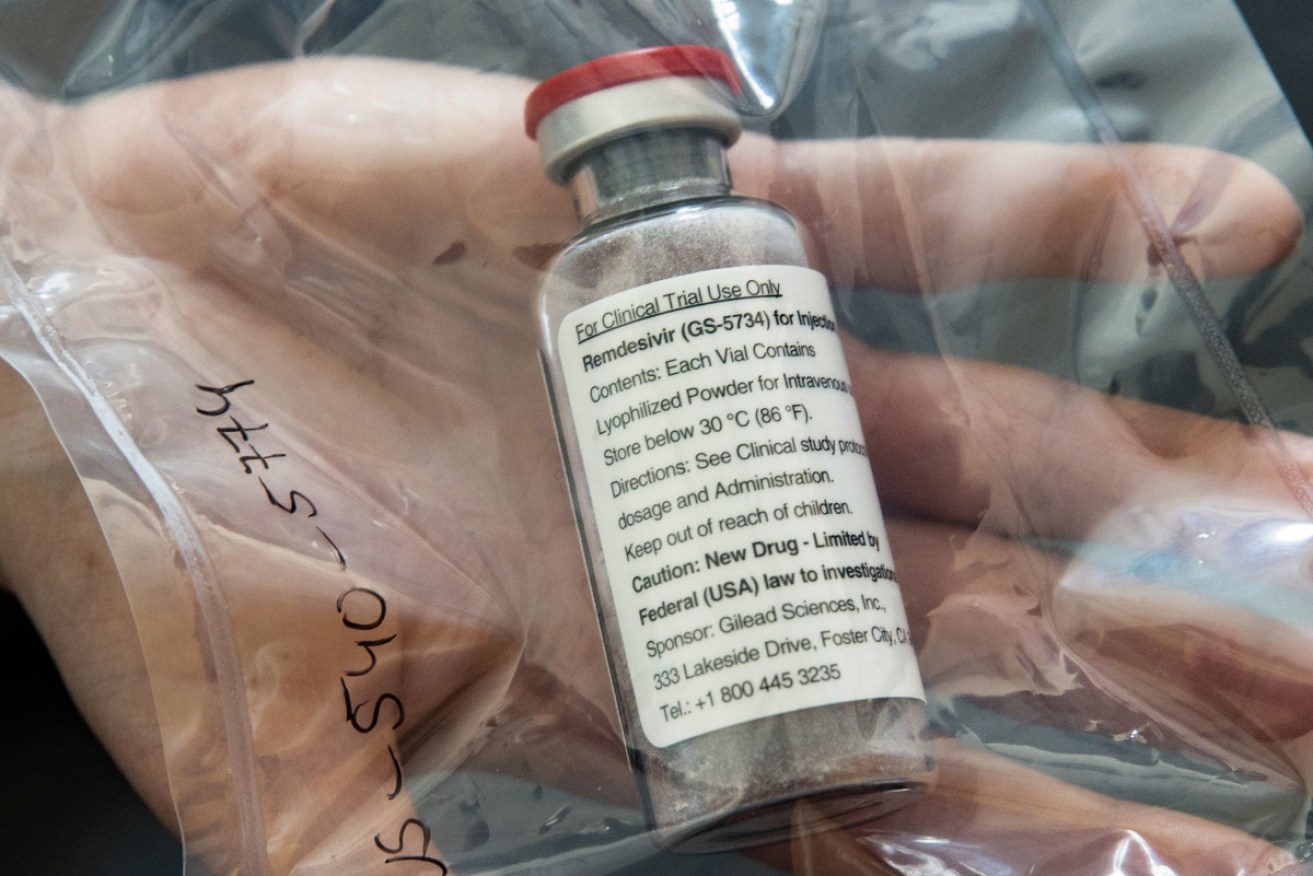

The anti-viral drug Remdesivir was originally developed for the treatment of ebola. Photo: Getty

The United States’ “emergency use” approval of the experimental antiviral drug Remdesivir to fight COVID-19 in patients made big news this weekend.

The approval was granted by the US Food and Drugs Administration two days after the National Institutes of Health’s clinical trial showed modestly promising results.

Ordinarily, this sort of news would come via a peer-reviewed journal. Instead, it’s occurred over three days, via a series of press releases.

On the heels of the USA, Japan has also announced it will fast-track a review of remdesivir so it can hopefully be approved for domestic COVID-19 patients.

Health Minister Katsunobu Kato’s stated: “I’ve heard that Gilead Sciences will file for approval (in Japan) within days.

“I issued an instruction so that we will be ready to approve it within a week or so.”

The US trial involved 1063 severely ill patients in dozens of hospitals around the world.

According to a statement from the US National Institute of Health, which funded the trial, patients given the drug, intravenously, over a ten day period, recovered 31 per cent faster than equally sick patients who were given a placebo.

In real terms, Remdesivir cut recovery time from a median of 15 days to 11.

The trial also showed a small improvement over mortality, but one not statistically significant.

The FDA, in the opening paragraph of the announcement, noted “there is limited information known about the safety and effectiveness of using Remdesivir to treat people”.

The listed possible side effects, including “increased levels of liver enzymes, which may be a sign of inflammation or damage to cells in the liver; and infusion-related reactions, which may include low blood pressure, nausea, vomiting, sweating, and shivering”.

The FDA authorisation means the drug can be used in hospitalised patients with severe symptoms, even in cases where COVID-19 is suspected, and not actually confirmed by testing. It can be given to adults and children.

The FDA drug had already approved the use of Remdesivir on compassionate grounds. People on the verge of dying were given the drug because there was nothing to lose.

The FDA announcement was entirely a surprise. The previous day, at the White House, Dr Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, described the trial results as “a very important proof of concept, because what it has proven is that a drug can block this virus”.

Dr Fauci conceded the quicker recovery achieved by the drug “doesn’t seem like a knockout 100 per cent,” and he was careful to make clear that Remdesivir isn’t a magic bullet or a cure.

And yet, he declared: “This will be the standard of care.”

And he’s correct, because so far there is nothing else that has worked in slowing or halting the disease.

Scientists tend to agree that the double-blind randomised controlled trial agree that the trial was well run (although the goal posts of the trial were reportedly changed), but there’s been a call for the trial data to be made public.

Gilead Science, the company that developed the drug, as a potential remedy for Ebola and hepatitis (both of those trials failed) is donating 1.5 million doses of the drug to hospitals.

Has this all happened too fast?

Dr Gaetan Burgio is head of the Transgenesis Core Facility in the Department of Immunology and Infectious Disease at the John Curtin School of Medical Research.

Responding to questions by email, Dr Burgio said:

“This is a very interesting question and there is a bit of debate on this. The US Remdesivir trial released from the NIH trial in a press release (not yet in a peer review publication) shows an acceleration for time to recovery (11 days instead of 14 days with placebo group) and reduction in mortality (not convincing).

“Indeed the time to recovery was assessed at day 28 in this trial. (A) Chinese trial published in The Lancet showed no difference in outcome between the placebo and the Remdesivir group. Overall it shows Remdesivir may work against the infection but not a silver bullet or a miracle drug. More details are needed to assess in detail this NIH trial.

“In this respect, yes I am a bit surprised by the rapid move to standard treatment and the fact it is made available under emergency provision. I would have expected more complete results from the respective arms (US, Europe, China) of this large trial before adopting such a move.

“I guess the pressure is massive in the US hospitals. Three days gain in recovery time might make a difference regarding the US situation and might ease the pressure in overloaded hospitals.”

Noting the “serious side effects”, Dr Burgio said the administration of Remdesivir has to be in light of the balance between risk and benefit.

“In short this means Remdesivir treatment might be beneficial to some, risky for others and this has to assessed carefully before initiating the treatment. Hence, its primary indication to a risk group (severe COVID19) where the benefits (time to recovery, mortality) outweigh the risks (severe side effects).”

Professor Stephen Evans, Professor of Pharmacoepidemiology in the Dept of Medical Statistics, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, in a posting at the Science Media Centre, said:

“This is the first evidence that Remdesivir has genuine benefits, but they are certainly not dramatic. We do not know what adverse events occurred and the long term prognosis is not yet known. A full assessment of these results cannot be made without seeing a full publication.”