Coronavirus treatment: This drug left babies deformed, now it’s a possible cure

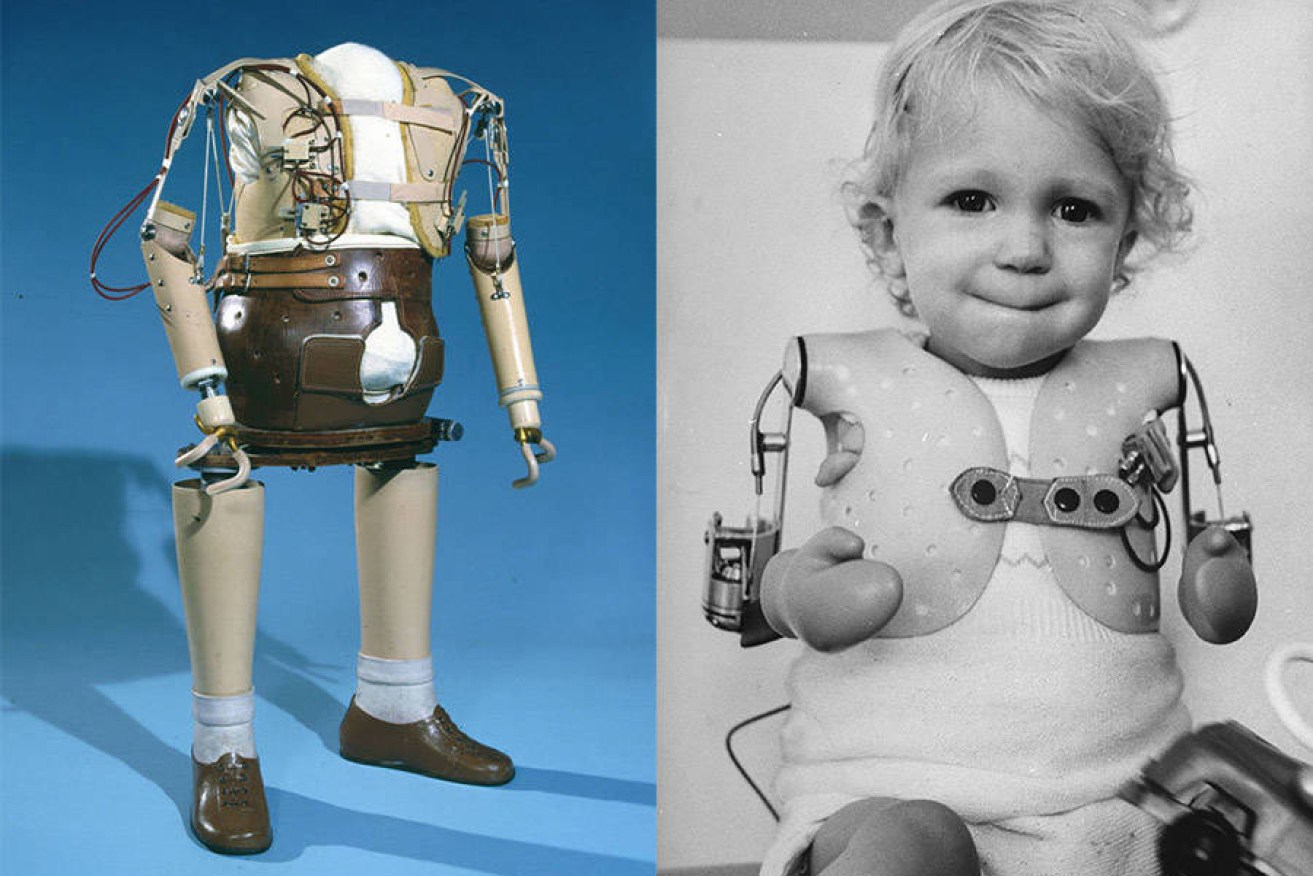

Thalidomide hasn't been rehabilitated in the public imagination, but it shows promise as an anti-inflammatory. Photo: Getty Images

Thalidomide, the notorious drug that caused thousands of babies to be born without arms or legs during the 1950s and early 1960s, is being investigated as a possible treatment for COVID-19.

Two clinical trials at Wenzhou Medical University will soon be recruiting participants to establish whether thalidomide, in tandem with low-dose hormones, might be an effective treatment for the often lethal form of pneumonia peculiar to severe cases of COVID-19.

One of the trials will include 100 participants who are sick with this pneumonia, and is presumably seen as a last ditch attempt to save lives.

From zero to hero, is it possible?

What a complicated story for the history books if thalidomide were to be found effective against a virus that has half the world in virtual hiding.

As The New Daily reported, in our explainer as to why developing a vaccine will take time, thalidomide was an anti-convulsive marketed to pregnant women as a safe sedative and as a treatment for morning sickness.

But clinical testing of the drug was limited. It was sold widely without prescription and subsequently 10,000 children were born with severe limb deformities.

The reputation of the drug was trashed, and for many people just the name thalidomide brings a dose of the horrors. The truth of the thalidomide story is that a good and versatile drug was given to the wrong patients with catastrophic results.

No doubt there is a widespread assumption that thalidomide was taken out of circulation.

Not true. Thalidomide continues to be rehabilitated as a treatment of great versatility. It’s been used as a treatment for lung damage caused by poisoning with the herbicide paraquat. Its anti-inflammatory properties are used to treat HIV-related mouth and throat ulcers, and for skin lesions caused by leprosy.

It’s had some success with blood and bone marrow cancers, such as leukaemia and myelofibrosis. One of thalidomide’s traits is that it works as an anti angiogenic, a drug that stops tumours from growing their own blood vessels.

What can it achieve against COVID-19?

On paper, thalidomide looks like it was designed to battle COVID-19. Aside from its anti-inflammatory properties, it also works as anti-fibrotic, a drug that inhibits fibrosis.

Hence it’s hoped that thalidomide might control lung inflammation and slow or halt the lung damage that is characteristic in severe COVID-19.

It already has form in treating a respiratory viral pandemic, the 2009 H1N1pdm09 influenza. It began in the US and, oddly, “primarily affected children and young and middle-aged adults,” according to the Centre for Disease Control.

Up to half a million people died from the (H1N1)pdm09 virus, yet the CDC advises that its impact on the global population during the first year was less severe than that of previous pandemics. However, the virus continues to “circulate seasonally in the U.S. causing significant illnesses, hospitalisations, and deaths.”

And it’s no where near as vicious as COVID-19.

As the summary from one of the trials at Wenzhou Medical University notes, thalidomide was proven “to be safe and effective in… severe H1N1 influenza lung injury.”

In these new trials, researchers are tracking fever, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, alleviation of cough, and duration of illness. And of course hoping that those very ill participants might pull through.