Coronavirus and alcohol: How to manage stress and keep your drinking in check

Turning to alcohol is not a good way to deal with the stress of the coronavirus pandemic. Photo: Shutterstock

Bottle shops remain on the list of essential services allowed to stay open and Australians are stocking up on alcohol.

In these difficult times, it’s not surprising some people are looking to alcohol for a little stress reduction.

But there are healthier ways of coping with the challenges we currently face.

Why do we drink more in a crisis?

People who feel stressed tend to drink more than people who are less stressed.

In fact, we often see increases in people’s alcohol consumption after catastrophes and natural disasters.

Although alcohol initially helps us relax, after drinking, you can feel even more anxious.

Alcohol releases chemicals in the brain that block anxiety.

But our brain likes to be in balance.

So after drinking, it reduces the amount of these chemicals to try to get back into pre-drinking balance, increasing feelings of anxiety.

People may also be drinking more alcohol to relieve the boredom that may come with staying at home without much to do.

What happens when we drink more?

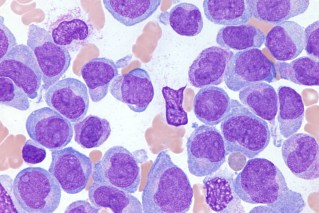

Alcohol affects your ability to fight disease

Alcohol impacts the immune system, increasing the risk of illness and infections.

Although the coronavirus is too new for us to know its exact interaction with alcohol, we know from other virus outbreaks drinking affects how your immune system works, making us more susceptible to virus infection.

So, if you have the coronavirus, or are at risk of contracting it, you should limit your alcohol intake to give your immune system the best chance of fighting it off.

The same applies if you have influenza or the common cold this winter.

Alcohol affects your mood

Drinking can affect your mood, making you prone to symptoms of depression and anxiety.

This is because alcohol has a depressant effect on your central nervous system.

But when you stop drinking and the level of alcohol in your blood returns to zero, your nervous system becomes overactive.

That can leave you feeling agitated.

Alcohol affects your sleep

Alcohol can disrupt sleep.

You may fall asleep more quickly from the sedating effects of alcohol, but as your body processes alcohol, the sedative effects wear off.

You might wake up through the night and find it hard to fall back to sleep (not to mention the potential for snoring or extra nocturnal bathroom trips).

The next day, you can be left feeling increasingly anxious, which can kickstart the process all over again.

Alcohol affects your thoughts and feelings

Alcohol reduces our capacity to monitor and regulate our thoughts and feelings.

Once we start drinking, it’s hard to know when we’re relaxed enough.

After one or two drinks, it’s easy to think “another won’t hurt”, “I deserve it”, or “I’ve had a huge day managing the kids and working from home, so why not?”

It’s easy to think, ‘another won’t hurt’ when we’ve already had a drink or two. Photo: Shutterstock

But by increasing alcohol consumption over time, eventually it takes more alcohol to get to the same point of relaxation.

Developing this kind of tolerance to alcohol can lead to dependence.

Alcohol ties up the health system

Alcohol-related problems also take up a lot of health resources, including ambulances and emergency departments.

People have more accidents when they are drinking.

And drinking can increase the risk of domestic and family violence.

So an increase in drinking risks unnecessarily tying up emergency services and hospitals, which are needed to respond to the coronavirus.

How to manage your alcohol consumption

Don’t stock up on alcohol.

The more you have in the house, the more likely you are to drink. Increased access to alcohol also increases the risk of young people drinking.

Monitor your drinking.

If you are getting on board with the new virtual happy hour trend, the same rules apply if you were at your favourite bar.

Try to stay within the draft Australian guidelines of no more than four standard drinks in any one day and no more than 10 a week.

Monitor your thinking.

It’s easy to think “What does it matter if I have an extra one or two?”. Any changes to your drinking habits now can become a pattern in the future.

How to manage stress without alcohol

If you are feeling anxious, stressed, down or bored, you’re not alone.

But there are other healthier ways to manage those feelings.

If you catch yourself worrying, try to remind yourself this is a temporary situation.

Do some mindfulness meditation or slow your breathing, distract yourself with something enjoyable, or practise gratitude.

Get as much exercise as you can.

Exercise releases brain chemicals that make you feel good.

Even if you can’t get into your normal exercise routine, go outside for a walk or run.

Walk to your local shops to pick up supplies instead of driving.

Maintain a good diet. We know good nutrition is important to maintain good mental health.

Try to get as much sleep as you can.

Worry can disrupt sleep and lack of sleep can worsen mental health.

Build in pleasant activities to your day.

Even if you can’t do the usual activities that bring a smile to your face, think about some new things you might enjoy and make sure you do one of those things every day.

Remember, change doesn’t have to be negative.

Novelty activates the dopamine system, our pleasure centre, so it’s a great time to try something new.

So enjoy a drink or two, but try not to go overboard and monitor your stress levels to give you the best chance to stay healthy.

If you are trying to manage your drinking, Hello Sunday Morning offers a free online community of more than 100,000 like-minded people. You can connect and chat with others actively managing their alcohol consumption.

If you’d like to talk to someone about your drinking call the National Alcohol and Other Drug Hotline on 1800 250 015. It’s a free call from anywhere in Australia. Or talk to your GP.![]()

Nicole Lee, Professor at the National Drug Research Institute (Melbourne), Curtin University; Genevieve Dingle, Associate Professor in Clinical Psychology, The University of Queensland, and Sonja Pohlman, Clinical Psychologist and Lecturer, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.