Scientists trial skin patch to treat peanut allergies in children

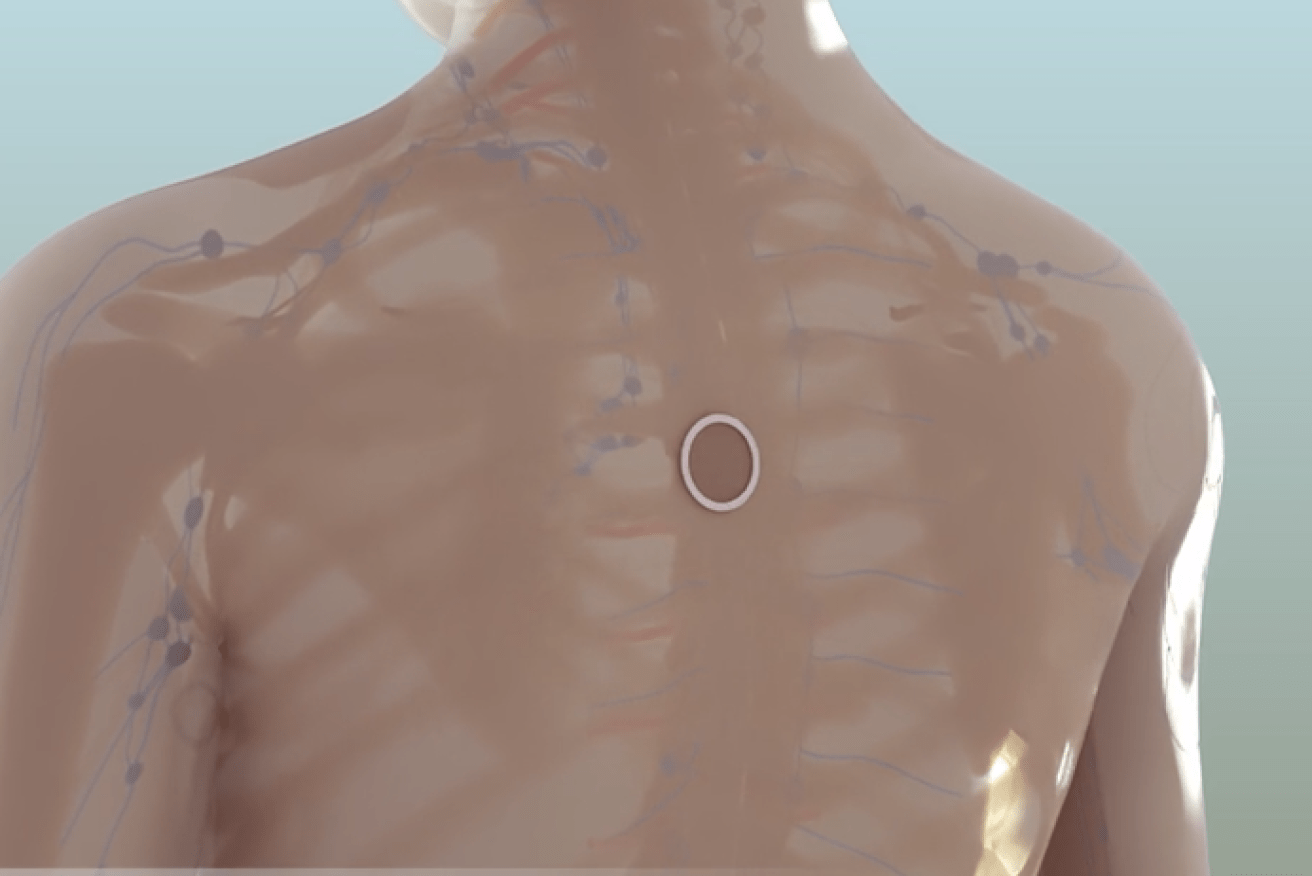

The 'peanut patch' enters the skin to activate cells that block allergic responses. Photo: DBV Technologies

Funded by French biopharmaceutical company, DBV Technologies, the study was conducted across 31 international sites including two hospitals and one allergy clinic in Australia.

Around 20 per cent of children will outgrow peanut allergies, however some will go on to develop severe, life-threatening reactions. Photo: Shutterstock

The authors said the results were “statistically significant”, but it did not quite reach US Food and Drug Administration recommendations – suggesting that the technology is still some way off from being rolled out widely.

“Clinicians will have to determine with patients whether a response of 35.3 per cent with the peanut patch is worthwhile,” wrote JAMA deputy editor, Dr Jody Zylke.

“In addition, the effectiveness, adverse events, adherence and durability of epicutaneous therapy must be weighed against the similar metrics with alternative types of therapy, such as oral immunotherapy,” the accompanying editorial said.

Oral immunotherapy, also known as desensitisation, involves giving gradually increasing amounts of food allergen under medical supervision. Though the potential treatment is currently undergoing trials, oral immunotherapy is currently not considered standardised or approved for use.

Peanut patch activates immune cells

For the “peanut patch” trial, scientists recruited 218 boys and 138 girls aged 4-11 years and diagnosed with peanut allergies – but without a history of severe anaphylactic reaction.

One group was randomised to receive the peanut patch, which was applied to the skin every day, while the other group received a placebo patch with no peanut protein.

According to the researchers, the peanut patch works by using the skin’s own immune properties to activate cells in the lymph nodes, which can go on to suppress and block allergic responses.

The patch technology is made up of different chambers, and contains a small amount of dry allergen in the condensation chamber.

When applied to intact skin, natural water loss from the skin activates the patch and releases the allergen in the chamber to the outermost layer of the epidermis.

The dry allergen enters the skin to switch off the allergic response. Photo: DBV Technologies

Anaphylaxis hospitalisations on the rise

Though severe reactions are rare, hospital admissions for anaphylaxis in the country has doubled in the last 10 years – with peanuts, milk and eggs listed among the most common triggers.

The risk of a severe reaction has prompted some parents to resort to hospital and GP carparks when feeding their babies peanuts and other known allergens for the first time, according to recent reports.

Parents are now encouraged to introduce babies to a wide range of foods, especially egg and peanuts, in their first year.

“The evidence that we have shows that, particularly if your child is at high risk of developing an allergy, the chance of them developing a peanut allergy and perhaps an egg allergy is reduced if you start to introduce these foods at around six months, but not before four months,” allergy specialist Dr Preeti Joshi told The New Daily