Syphilis returns to Queensland, and it’s killing babies

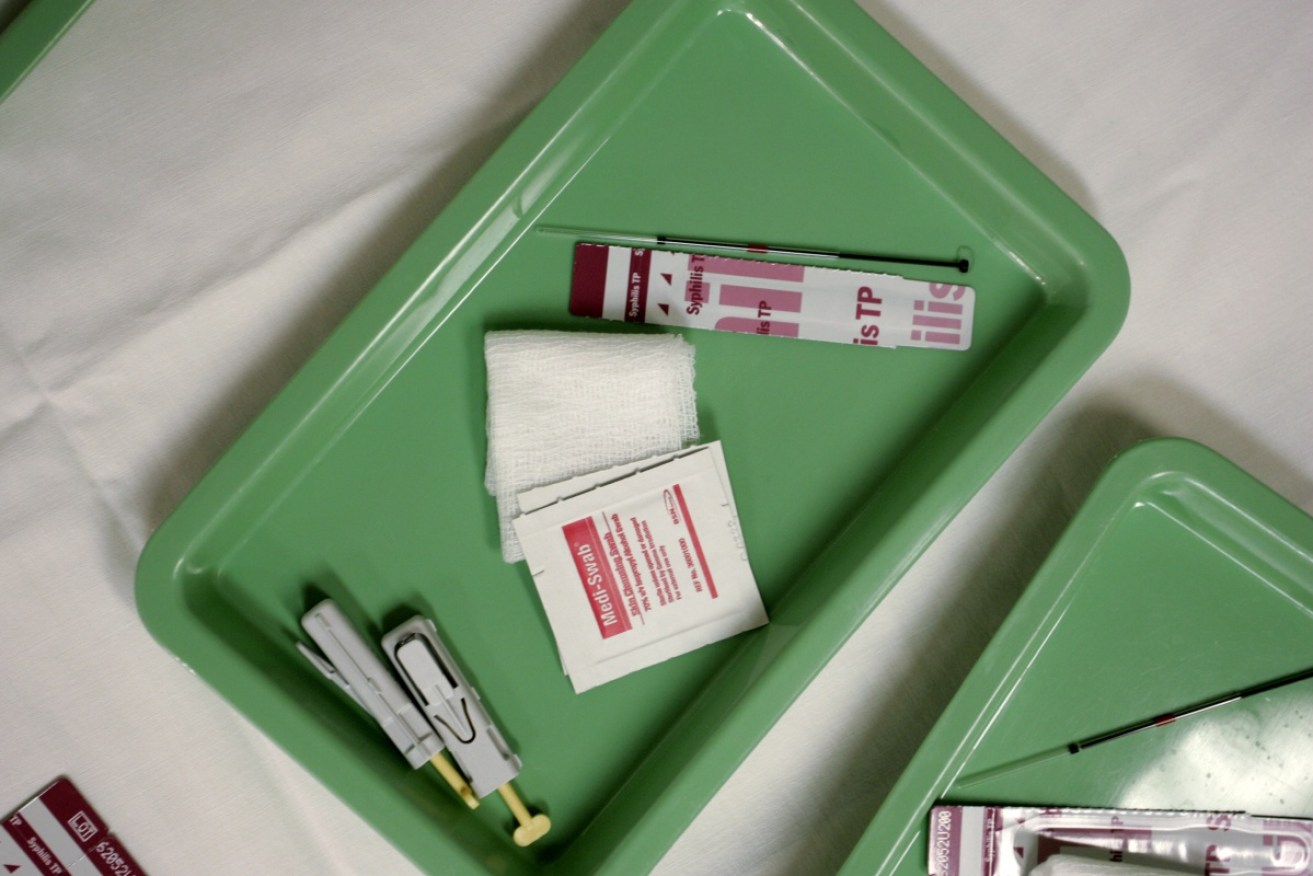

A syphilis medical testing kit. Photo: AAP

A disease that once sent kings mad in medieval times is now rife again in epidemic proportions, and is killing Queensland babies.

In the last six years, six babies have died in the state from syphilis – a sexually transmitted disease that was nearly eradicated in the early 2000s.

In 2008, two cases were diagnosed in Queensland, and in the decade since, more than 1100 other cases have been recorded in the north of the state, with about 200 new presentations each year.

The numbers continue to grow, despite penicillin being a cheap and effective cure.

Cairns sexual health clinician Darren Russell works in the epicentre of the outbreak and said it was “out of control”.

“So from almost eradicating it, it’s turned into one of the biggest epidemics in recent history,” Dr Russell said.

“Here we are with a good test, a good treatment and we still can’t get on top of it. I’m appalled it’s still happening.”

How did this happen?

The outbreak started in the Indigenous community of Doomadgee, on the Gulf of Carpentaria, in 2011 with a handful of cases.

At the time, sexual health services across Queensland were cut by the Campbell Newman-led Queensland government, and health workers claimed the opportunity to stop the escalation was missed.

The number of cases quickly spiralled out of control because of the transient nature of people in Indigenous communities, and the outbreak spread across Queensland, into the Northern Territory, and into South and Western Australia.

Health workers say any current action to control the outbreak is years too late, which Federal Indigenous Health Minister Ken Wyatt acknowledged.

“Well somebody missed the boat because it should not have happened that way,” he said.

“For it to have gone so long is not acceptable.

“In a day and age like ours, when you hear that you think, what the hell has happened? How was this situation allowed to happen?”

It took at least five years from the start of the outbreak for both the State and Federal Government to commit specific funding for the issue.

In 2016, the Palaszczuk Government promised a $15.7 million campaign to increase awareness and testing.

Queensland Health Minister Steven Miles said progress was stalled as a result of the Newman funding cuts.

“It’s no wonder the current rates remain regrettably and unacceptably high,” he said.

So what is syphilis?

People infected with syphilis often develop lesions, rashes and sores across the body.

The infectious illness became infamous for its devastating effect on kings in the 16th and 17th centuries, where it caused traumatic disfigurations and affected neurological functions.

Syphilis had been known as ‘the great pox’. Photo: Wikimedia

It was known as ‘The Great Pox’, and sent them mad.

Today, the outbreak has been highly dangerous for pregnant women, who have passed on the infection to their baby through the womb.

“The death rate for babies can be 50 per cent or more in that situation,” Dr Russell said.

“And for those babies that do survive, there is the potential for long-term problems like blindness, deafness and cognitive issues.”

Blood testing for the disease is strongly encouraged but is not considered to be hugely successful.

Aboriginal Health worker Neville Reys from Wuchopperen Health, said testing – and therefore treatment – was hindered because of shame and stigma.

“It’s almost like taboo and people really don’t want to share that they got it, the shame factor around it,” he said.

“Syphilis can draw out up to six months before you really realise that you have got it, and in that timeline there’s lots of sexual activity, so it can be spread around really easily.”

‘Rapid’ test kits to deliver immediate results

Last year, the Commonwealth committed its first dedicated package of funding to tackle the outbreak, with $8.8m for a new type of testing set to deliver immediate results.

62,000 ‘rapid’ test kits will be rolled out across Cairns, Darwin and Townsville from next week, to eliminate the two-week turnaround currently required for testing and treatment.

Mr Wyatt said he hoped the new testing regime would be more easily accessed by a transient population, and prevent any future deaths.

“Those six [babies] deserved better,” he said.

“Let’s be proactive and work as a state, Commonwealth and with the Aboriginal community to make sure this doesn’t happen again.”