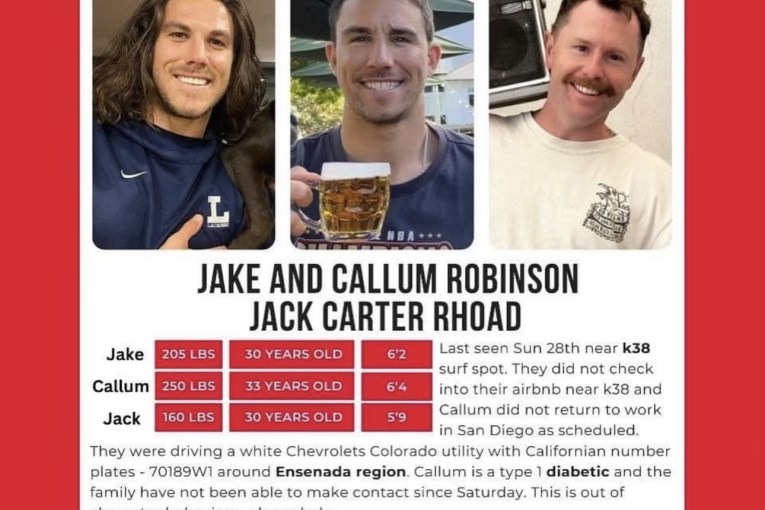

Study indicates Caesarean babies ‘more susceptible to health complications’

Caesarean births may be more likely to result in health complications. Photo: Getty

A global study involving Australian mothers and their babies has found “significant links” between medical birthing interventions like caesarean sections and childhood health problems.

A team of researchers from the UK, Ireland, Amsterdam, New South Wales and South Australia analysed nearly half-a-million births in NSW between 2000 and 2008 from healthy women with full-term pregnancies without complications.

The study, published on Monday in the journal Birth, involved an analysis of health records from birth to the age of five years.

Researcher Charlene Thornton from Flinders University said rates of adverse health outcomes were up to three times higher in infants born through interventions than those who were not.

“What we found was that infants who experience instrumental birth – so forceps or a ventouse birth – following an induction of labour had the highest risk of getting jaundice and having feeding problems,” Dr Thornton said.

“We also found that infants born by caesarean section had higher rates of being cold – so hypothermia following birth – and that children … up to five years of age, that were born by emergency caesarean section … had the highest rates of metabolic disorders, so the higher rates of diabetes and obesity.”

Dr Thornton said overall, babies born through any type of intervention had a greater chance of developing respiratory infections, metabolic disorders and eczema.

“They were quite significant findings and this is a really detailed data set that we use and we link it with different types of data sets to look at long-term health outcomes,” Dr Thornton said.

Professor Hannah Dahlen from Western Sydney University said the study added to the “mounting scientific evidence suggesting that children born by spontaneous vaginal birth, without commonly used medical and surgical intervention, have fewer health problems”.

“Across the board, the results indicate that the odds of a child developing a short or longer-term health problem significantly increase if there was a medical intervention at the time of their birth,” Professor Dahlen said.

‘More research needed’ to look at longer-term trends

Dr Thornton said the current hypothesis was that vaginal births provided an important opportunity to create a healthy microbiome.

“There’s something going on with the baby’s microbiome and there’s something they’re missing out on being born in ways that aren’t considered normal,” he said.

“Anything that changes that normality or changes that process actually affects us not just in the short term but in our long-term health as well.”

Mothers and their babies were only included in the study if the women were aged between 20 to 35 and gave birth at 37 to 41 weeks of gestation to a single baby within a normal weight range.

The women also did not smoke or take drugs and were considered “healthy” mothers with low-risk pregnancies.

Dr Thornton said more research was needed to look at even longer-term health outcomes in children.

“These are things that we didn’t know previously, we know about short-term outcomes but not long-term outcomes and we’re seeing more and more intervention these days — higher caesarean section rates — without really knowing what’s happening long-term to our babies,” she said.

“As time goes on we have more and more data to look at so we’re going to look next at 10-year outcomes and see what happens to babies in 10 years as well.

“It’s such a significant issue with changing rates of all these types of interventions and then changing outcomes for babies, it’s just too important not to do this research.”