‘Blackfishing’: The social media influencers trying to be more black

Christina Sikalias, with 566,000 Instagram followers, has been accused of "blackfishing". Photo: Instagram

Black, tan or blackface? That is the debate sparked by a new skin-darkening social media trend that has seen digital influencers accused of pretending to be black.

The practice has been coined “blackfishing”, with accusers claiming women are taking on black characteristics such as skin colour, corn rows and full lips in a form of cultural appropriation.

Blackfishing emerged last month when Twitter users called out white models with seemingly dark skin, but the claims have been strongly denied by those at the centre of the controversy such as Swedish model Emma Hallberg, 19, who attributes her tones to sun tanning.

Australian beauty influencers such as Christina Sikalias and Dani Mansutti have been accused of cultural appropriation.

In a number of posts on Ms Sikalias’s Instagram account, the makeup artist poses with makeup that is several shades darker than her earlier honey tones.

Christina Sikalias after her transformation. Photo: Instagram

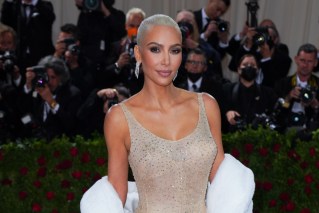

The Melbourne-based influencer with 566,000 followers is a Kim Kardashian look-alike who has been under fire for cultural appropriation for wearing ethnic hair braids.

Christina Sikalias’ usual look. Photo: Instagram

Ms Mansutti also entertains her 493,000-strong audience with photos in which she is eschews her characteristically blonde hair and light skin.

Dani Mansutti before. Photo: Instagram

Dani Mansutti after: Photo: Instagram

The New Daily contacted both beauty influencers for comment on their changing appearances but received no response.

Cultural appropriation is defined as taking or using things from another culture, especially without showing you understand or respect that culture – particularly a dominant culture appropriating a minority or oppressed one.

Whether the skin-darkening trend is a case of over-the-top tanning or a deliberate attempt to look black, both motivations have raised concerns from critics about the message it sends to impressionable followers.

RMIT University senior lecturer in marketing Dr Lauren Gurrieri told The New Daily it was “concerning” that beauty bloggers, who had significant influence on their fans, were encouraging such physical transformations.

“Apart from the political aspects [of cultural appropriation], the fact that they are so dramatically changing their appearances from their natural look sets a tone that you need to change yourself and that is concerning,” Dr Gurrieri said.

“What makes it uncomfortable is, to me, darkening the skin: it smacks of blackface and the connotations associated with that.

“[Blackfishing] is profiting and benefitting from appropriating aspects of a culture without having the broader experience and inequalities faced by that culture.

“It’s divorcing those aspects of the culture from the meaning and is moving into charged political territory.”

Dr Gurrieri said digital influencers were “micro celebrities” who shaped ideals of body image and profited from brands using their connections with followers to reach millions of potential customers.

“Often digital influencers are white and young and getting endorsement deals, therefore they could be taking away opportunity from black women being able to do that. There is a sense of white privilege,” she said.

Dr Arianda Matamoros-Fernandez, a lecturer in digital media at Queensland University of Technology (QUT), said cherry-picking black physical traits followed on from existing examples of cultural appropriation – white people speaking African-American vernacular, for example, or using minority cultures’ aesthetics and practices such as ethnic dress and hairstyles.

“By practising blackfishing, white people are able to play blackness without having to deal with the everyday discrimination still faced by black people in many levels of society,” said Dr Matamoros-Fernandez, who researches changing dynamics of race and racism in social media.

“As critical race theorists and whiteness studies scholars have argued, attempting to darken one’s skin to pass as black reproduces and perpetuates white privilege.”

Dr Matamoros-Fernandez said digital tools such as photo filters made blackfishing easier, while the attention-seeking economy of social media “amplified” the practice, leading to further alienation.

“The fact that white influencers engaging with blackfishing are making profit of it is the second big problem of this discriminatory practice,” she said.

“Attention is a key resource of influencers, and white influencers are using blackfishing to increase their audience engagement [likes, shares, comments], which often results in economic revenue for them.

“Here again, influencers engaging in blackfishing perpetuate systems of white privilege and contribute to alienate those whose culture is being appropriated.”