Young Rupert: The origin story of Murdoch’s meteoric rise

The story of how Rupert Murdoch came to such lofty power.

Meticulously researched, Young Rupert: The Making of the Murdoch Empire is both densely detailed and a rollicking read, taking readers from the battlefields of Gallipoli to the boardrooms of Australia’s newspaper moguls, to the Adelaide courtrooms where the most dramatic media trial in the state’s history took place.

It goes some way to shedding light on how Rupert Murdoch, a relatively undistinguished young man thrust into business leadership by the sudden death of his powerful father, built a global empire from modest beginnings in Adelaide.

But not all the way.

Murdoch remains an enigma in Marsh’s telling – at turns shrewd then barely competent, opportunistic and careful, a monopolist and a spruiker for competition (when it suited him), both loyal and also ready to cast aside friends in the interests of empire-building, despite his 1958 quote that serves as the book’s epigraph: “There is no attempt to create an empire or anything like that – it would not interest me.”

Marsh begins with Sir Keith Murdoch, Rupert’s father – a friend to prime ministers, in many ways the generator of the Anzac myth (due to his somewhat sketchy famous dispatch from Gallipoli), a stealthy business operator, and an anxious father.

Sir Keith’s death at the age of 66 left his flailing media assets in the hands of young Rupert, very much an unknown quantity including in the critical eyes of his father.

After a middling performance at prestigious Geelong Grammar, Rupert nevertheless found his way to Oxford, where he was clearly an outsider.

Although much has been made of Murdoch’s left-wing tendencies at university, he comes off in Marsh’s telling as a somewhat flaky figure, neglecting his studies, gambling, zooming (badly) around the continent at the wheel of a car that he drove into the ground, causing persistent worry to his father.

Courage becomes a casualty

His father’s death left the young man with only one substantial asset – Adelaide-based News Limited and its key titles in the city, afternoon paper The News and Sunday’s The Mail.

The News is at the heart of the book, and Marsh brings vivid detail to life in the North Terrace newsroom of the tabloid, where Rupert – dubbed not entirely flatteringly the Boy Publisher – and inspirational editor-in-chief Rohan Rivett proceeded to shake up Adelaide’s power dynamics, at significant personal cost to the lanky flame-haired editor.

Rivett had been appointed by Sir Keith to add some spark – and profitability – to The News. With the younger Murdoch relocating to Adelaide, the paper began to create a bigger stir, butting heads with the establishment Advertiser, which had a cosy relationship with the state government, and the entitled gents of the Adelaide Club.

Rivett, a Victorian-born journalist who had survived the notorious Burma Railway as a prisoner of war, was incensed by both the backroom deals which saw The News frozen out of advertising deals and the broader power dynamics of SA.

“The deep ties between the city’s political and commercial establishment, and a morning paper that seemed happy to exploit its influence with zero accountability, infuriated Rivett,” Marsh writes. “He had waded into a cosy, highly concentrated media landscape that had been entrenched for 20 years.”

Marsh, who has a keen eye for irony and an elegant turn of phrase, points out that Sir Keith was reluctant to unravel this system, as he had helped make it that way from inside the Melbourne boardroom of the Herald and Weekly Times newspaper group that owned The Advertiser.

Young Rupert, though, was a different proposition.

The heart of the book is propelled by these dynamics, as Rupert Murdoch and Rohan Rivett – a much more vivid character than his boss, perhaps due to the co-operation of his family and the size of the archive accessible to Marsh – confront powerful forces. (Rupert Murdoch and his family didn’t co-operate in the book.)

Key to the emerging drama is the case of Rupert Max Stuart, an Indigenous man condemned to hang for the shocking murder of nine-year-old Mary Hattam in Ceduna in 1959. It was taken up with gusto by The News, which sensed injustice. Under pressure, long-term Premier Tom Playford – unaccustomed to scrutiny from the press – ordered a royal commission.

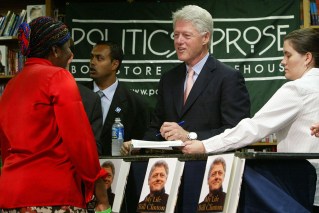

Murdoch’s ability to grow his business is detailed in the book. Photo: Getty

After some pointed criticism of the judges overseeing the inquiry, The News and Rivett were targeted with the archaic charge of “seditious libel”.

Despite its rare use, the charge carried the risk of serious jail time.

Marsh’s account of the case, its personal consequences and what it revealed about the machinations of the newsroom is the stunning centrepiece of the book, even as Murdoch fades into the background. It’s in this case, though, that the young publisher shows his capacity for throwing aside loyalty and stepping in and out of the shadows in the name of business advancement. Marsh’s revelations on this point are fascinating.

The author’s archival work on some other points are worth mentioning.

His detailed account of Murdoch’s ham-fisted attempts to garner a monopoly in Adelaide on the emerging technology of television reveals the future mogul’s ‘flexible’ approach to competition. After earlier railing against monopolies, in the interests of his Adelaide newspaper assets, he then argues that competition is a bad thing, because it lowers standards. Despite his amateurish public performance on the TV issue in front of a formal inquiry, he still got his way in the end.

The arc of Murdoch’s relationship with Rivett is the book’s most poignant. I’ll leave it to readers who don’t know Rivett’s story to discover for themselves how it all ends. Even if you do know the broad brush strokes, the denouement packs a punch.

It’s that sort of book: It combines detailed history, including fascinating side journeys – into Murdoch’s personal reportage on outback Aboriginal communities (eye-opening in many ways), a firebrand activist’s tragic-heroic trajectory, a literal fist-fight between Packer and Murdoch interests to gain control of a Sydney press – with the narrative drive of a thriller.

In the end, though, this reader had a sense of sadness about what could have been for Adelaide.

Used and abandoned

It’s no spoiler to reveal that Murdoch eventually fully swallowed his establishment rival in Adelaide, The Advertiser, along with the rest of the Herald and Weekly Times stable where his father had once operated in a strange, ruthless fashion, carving out essentially a rival newspaper group from within the boardroom.

As Marsh notes, The News was once a well-oiled operation and serious nursery for journalists of substance, sending skilled “Murdoch men” into the growing global empire.

In the late 1980s, though, The News was cast aside in favour of Murdoch’s new prize – long-coveted control of the HWT group.

The Advertiser, after a brief flurry challenging the top end of town over the State Bank disaster, settled into a period of comfortable monopoly – essentially what it had enjoyed way back in the 1930s under Sir Keith’s Melbourne-based syndicate.

The News, after a management buyout, collapsed and was gone forever.

Murdoch moved on, some would say to tragic consequences, to build substantial interests on both sides of the Atlantic, most notoriously his red-top English papers and the cynical right-wing US cable news network, Fox.

The 93-year-old remains at the helm of the empire, and remains the dominant figure in the Australian and South Australian media landscape.

The world awaits what will happen next.

Marsh’s meticulous research makes it clear what Rivett believed would occur to the media group’s shares without Rupert at the helm.

This is a distinguished work – essential for anyone who wants a greater understanding of Murdoch, his empire, and the contemporary history of South Australia.

Young Rupert, Scribe Publications, $35, was released on August 1. Next week, InReview will publish an extract from the book that reflects on the relationship between Rupert Murdoch and Rohan Rivett.

Disclaimer: David Washington is acknowledged in the author’s note in Young Rupert. He provided a copy of a 1980s news article he wrote that formed part of the research.