‘I defied all of these expectations’: Anne Summers’ on fame, fortune and family

Feminist Dr. Anne Summers has had a career most could only dream of. Photo: Supplied

“I was born into a world that expected very little of women like me,” writes Dr Anne Summers, AO, in her newly-published autobiography, Unfettered And Alive.

“We were meant to fade into invisibility as we aged. I defied all of these expectations.”

And how.

The trailblazing feminist, 73, lays out her stellar career as a journalist, author, policymaker, publisher and political activist, among other accomplishments, in her candid and inspiring memoir, which also explores her strained relationship with her father, Austin.

In the following exclusive extract, Summers takes us back to 1988, when she co-engineered Fairfax’s $20 million purchase of Ms, the women’s magazine co-founded by Gloria Steinem, and moved to New York to become its editor-in-chief.

It was also the year she reconciled with her father, who was dying of prostate cancer back home in Adelaide.

***

The year my father died was the same year that I became a business owner in New York, raised what seemed (then anyway) a huge amount of money on Wall Street; got a Green Card which gave me permanent residence in the United States; and become a well-known and, for a short time, sought after person in the place where, according to the song, if you can make it there …

“My interview with Julia Gillard at the Sydney Opera House on 30 September 2013 was her first public appearance after she was dumped as Prime Minister and was a highly emotional and engaging event.” Photo: Unfettered and Alive

I was unrecognisable as the sullen teenager who had stirred up so much anger in him. Nor was I any longer the ‘ratbag’ radical of the 1970s who enraged him.

I’d met my parents once in Sydney, after I’d been to a political demonstration, and as I stomped across the grass in Hyde Park to our meeting point, I could see the disappointment – or was it disgust? – on their faces.

Their only daughter – and look at her.

Both he and my mother had had such conventional hopes for me, about the sort of person I might marry. They’d hoped for a doctor or a lawyer, someone whose status I would automatically assume. They had never expressed any ambition for me.

My father had actually told me, while I was a teenager, that sending me to university would be a waste of money. Not that it cost him anything when I finally made it there, thanks to a Commonwealth Scholarship and the fact that I had totally supported myself since the age of 14.

Now, both my parents were proud of me – of what I was doing and how I looked. I had my share of designer clothes, although many of them had been bought cheaply from Loehmann’s, their labels snipped off. My photograph was in the New York Times, in New Yorker and Time magazines, and similar arbiters of achievement.

I was under orders to send home copies of all such mentions, and my mother meticulously documented my life.

After his death, I discovered that my father had fixed to the wall beside his bed a framed glam photo of me, taken in 1983 by Australian Vogue. This was the daughter of his dreams.

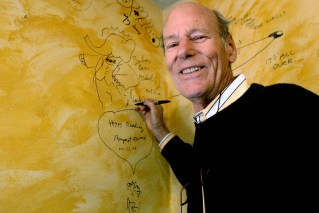

“After I was appointed to run the Office of the Status of Women for the Hawke government, Vogue did a profile of me accompanied by a glamorous photo shoot.”

In July 1988, after Sandra [Yates] and I had done the deal in New York, he’d written a letter telling me how proud he was of me. I flew to Adelaide for my brother Paul’s wedding on 20 August.

My father looked wretched: he was gaunt and slow to move. Again, we did not talk. I did not even acknowledge that he had written to me. But back in Sydney, just before I returned to New York, from a friend’s house in Rozelle, sitting on the floor to be close to the telephone, I rang.

Finally, we had the conversation that had been building up inside both of us for almost three decades. It was still hard. Neither of us was accustomed to expressing towards each other any feelings, except hostility.

But we both knew this might be the last time we talked and perhaps it was easier that we could not see each other.

He raised it first. He said he knew that we’d had ‘difficult periods’ in the past, and he got upset as he tried to say how sorry he was for the way he’d treated me.

I listened with astonishment, and was so overcome with unfamiliar emotions that I barely knew how to respond. I kept saying, “It’s all right. I forgive you. I forgive you.” And, in the end, sobbing, just before I hung up: “I love you.”

Back in New York I wrote to him.

I told him how much I’d appreciated his letter and, especially the business advice he had given me. “It is pretty ironic, as I’m sure you appreciate”, I’d written, “that of all your kids I am the one to end up a capitalist.”

I assured him that the “difficulties” we had had were “long forgotten” and that he should not “harbour any feelings of remorse about that time”.

Then, not knowing if I even believed what I was saying, I set out for him why I thought he should be proud of his life, of his family, of his accomplishments. I told him that he and I were more alike than we had ever wanted to acknowledge.

I told him that as I wrote, I was listening to Kiri Te Kanawa singing Verdi: “My love of opera is something else I learned from you.” I told him that I admired how he had finally been able to stop drinking, acknowledging how hard that must have been for him, and how glad I was that I’d been able to play a small part in helping it happen.

“I visited my parents in Adelaide as often as I could after my father’s cancer diagnosis in 1986 and before his death in 1988, including this trip in May 1987.”

“I would like to be able to help you now,” I wrote, “as you deal with a difficult and painful illness.”

I told him he needed to accept that he was sick: “As you have shown in the past, you have the strength and character to deal with it”.

I folded the four sheets of heavy cream paper and placed them in the matching envelope, with its maroon-coloured tissue lining.

I addressed the envelope, using the same Montblanc fountain pen with my signature brown ink that I’d used for the letter and stamping it Air Mail, sent it on its way.

It arrived the day after he died.

I made it back to Adelaide [for his funeral] with just hours to spare, arriving at St Ignatius Church in Norwood.

There, were just a few people he’d worked with, a couple of AA mates and other friends, together with members of both his and my mother’s families, but my father would have been tickled pink to know that among the small number of floral tributes laid beside his coffin was one from Gloria Steinem.

Edited extract from Unfettered and Alive, by Anne Summers, Allen and Unwin, published October 24.

For info on Anne Summers’ tour visit: https://allenandunwin.pgtb.me/Mvbf4n#Events