The New Look: Apple TV drama shows how Dior brought optimism to a war-weary world

Apple TV+

Christian Dior’s 1947 “new look” – a collection of extravagantly brimmed hats, wide full skirts and cinched waists that drew attention to the female silhouette – signalled a new post-war era of optimism, pleasure and a sense of life returning to normal.

Dior’s haute couture collection remains a historical moment for post-war fashion, and lends its name to Apple’s new 10-part series.

The drama explores the state of Parisian couture in the final year of World War II and the years that followed through the lives of important designers.

This includes Dior and his contemporaries Coco Chanel, Pierre Balmain, Cristóbal Balenciaga, Lucien Lelong, Hubert de Givenchy and Pierre Cardin.

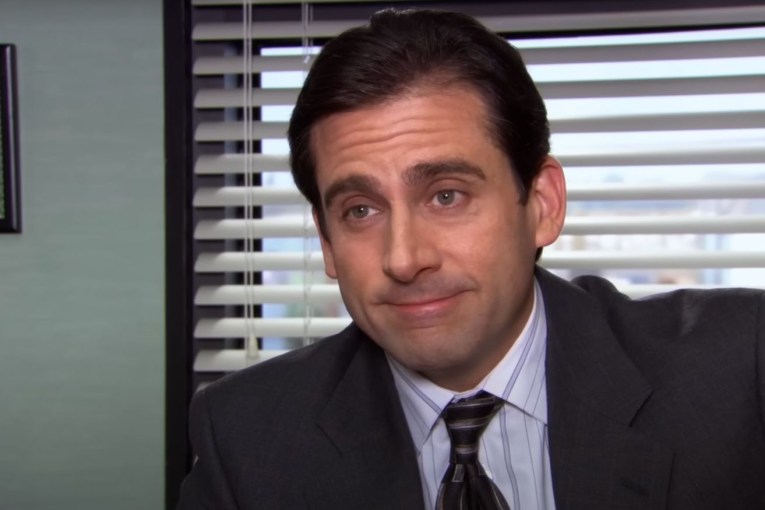

Ben Mendelsohn as Christian Dior in Apple’s new drama. Photo: Landmark Media

Inspired by true events, the series stars Ben Mendelsohn as Dior, Maisie Williams as his younger sister Catherine, Juliette Binoche as Chanel, John Malkovich as Lelong and Glenn Close as the US Harper’s Bazaar fashion editor Carmel Snow.

The series begins after Dior’s huge success with the launch of his new look collection in 1947 with a Q&A at Sorbonne University in Paris.

After a riotous welcome from an audience of fashion students, the Frenchman explains: “For those who lived through the chaos of war, creation was survival.”

This is the theme of the series, revealed in flashback: How the destruction and horror of war affected the world-renowned Parisian fashion market – its designers, design houses, those who worked within the industry and the people of France themselves.

A central character on and off screen is Dior’s courageous sister Catherine, who is little known and rarely mentioned in the history of Dior’s life, beyond the naming of his perfume Miss Dior in her honour in 1947.

Throughout the series her fate is emblematic of the French population’s experience of occupation, and is depicted as the driving force of Dior’s dedication to couture.

French fashion during wartime

In June 1940, Nazi forces took control of northern and western France and its textile industry.

By November 1942 the remainder of southern and eastern France fell to the German army.

Prior to the occupation, many non-French designers, such as Elsa Schiaparelli, left the country for London, New York and Los Angeles in anticipation of war.

Once Nazi forces invaded, Paris and its international fashion markets were effectively cut off from the rest of the world.

The couturier Lucien Lelong occupies an important place in the series as Dior’s supportive employer – although much more could have been made of the key role he played in keeping Parisian couture open for business.

“Creation cannot stop the bullets, but creation is our way forward”, the character states. True to his word, as war raged, Lelong employed some of the most successful post-war designers in his atelier including Dior, Pierre Balmain and Hubert de Givenchy.

Lelong was elected president of the prestigious Chambre Syndicale de la Couture in 1937, and faced down threats from the Nazis to move the entire couture industry to Berlin and Vienna.

He negotiated, persuaded and outmanoeuvred the Germans throughout the war by insisting that couture – and the domestic textile industry it depended on – was uniquely French and therefore could not be replicated elsewhere.

The couture industry experienced severe rationing of fabric. But the series successfully demonstrates that Paris fashion continued with determination and innovation.

As fashion designers were forced to limit the amount of material they used, unnecessary decorative additions such as ruffles and pockets became expendable. Instead, wartime couturiers turned to embroidery and beading for decoration – trends that continue to characterise haute couture today.

Christian Dior in 1953. Photo: Granger – Historical Picture Archive

The rival ‘American look’

With the end of the war and freedom from Nazi occupation, Paris fashion was in a fight for its life.

Its biggest rival was the American ready-to-wear apparel industry, an aspect of the story this new series dramatises to great effect.

Though the American industry also faced fabric rationing during the Second World War, it was not occupied, and the restrictions weren’t as debilitating. While Asian silks and Italian wools were no longer available, good American cotton was plentiful.

A new generation of American designers came into their own with a homegrown design aesthetic. In 1945 Dorothy Shaver, vice-president of the luxury retailer Lord & Taylor, developed a marketing campaign around the phrase “the American look”.

This successfully encouraged American women to remember their roots and not return to the collections of the newly liberated Paris fashion houses.

Dior’s beacon of hope

Dior’s 1947 Carolle collection, was renamed the “new look” at first viewing by American fashion editor Carmel Snow.

Snow claimed it represented the creation of a new femininity, which Dior would later call “the golden age of couture”.

Dior designs from 1954. Photo: Chronicle

It stood in stark contrast to the austerity wardrobes of wartime Europe and America – wardrobes millions of women around the world would continue to wear in everyday creative adaptations and alterations for years to come.

In my view, leaving the proper substance of the new look story until episode eight of a 10-part series suggests a lack of balance, and makes the title of the drama feel a little misleading.

Despite the voiceover in the trailer saying so, Dior’s new look did not reinvent fashion. Rather, it celebrated the end of the grim years of wartime trauma, misery and lack.

What Dior did through his collection was usher in a sense of optimism that women could once again enjoy the pleasure of pretty, feminine clothing that reflected individuality and joy.

The rationing of food, fabric and everyday essentials continued into the 1950s, but this new look offered an exhausted Europe the sense that life would begin once more.![]()

Elizabeth Kealy-Morris, senior lecturer and researcher in Dress and Belonging, Manchester Fashion Institute, Manchester Metropolitan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.