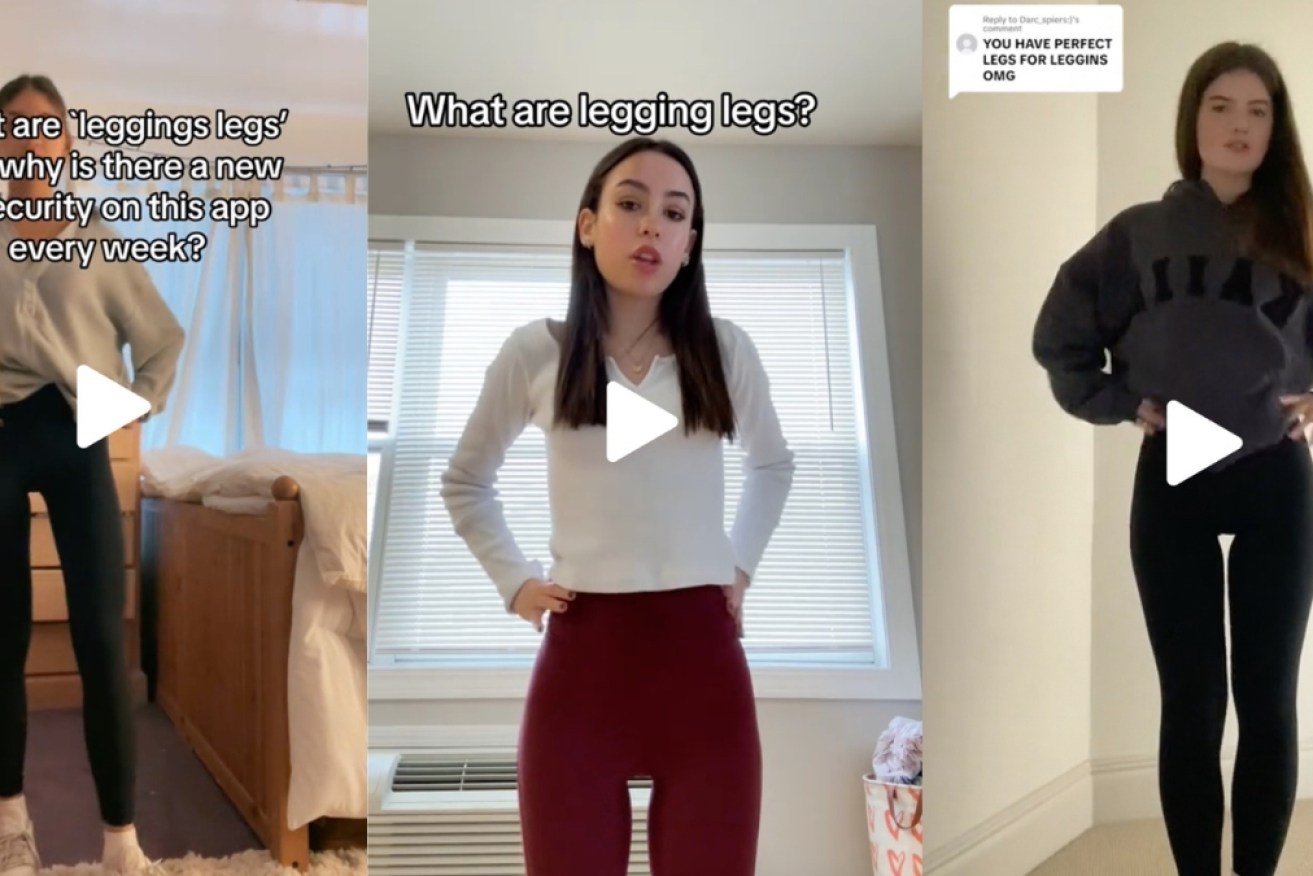

‘Legging legs’ proves social media’s days of body-image toxicity are far from over

'Legging legs' have taken TikTok by storm. Photo: TND /TikTok/@miakunis11/@fl0rabutter/@sydneymarie469

Whether it’s thin legs, perfectly defined abs or clear skin, the promotion of idealistic bodies is nothing new on social media – but the latest trend has been met by almost-instantaneous backlash.

In an apparent resurrection of the 2010s ‘thigh gap’ Instagram and Tumblr trend, many female TikTokers have been discussing how good – or bad – they look in tight leggings, using the term ‘legging legs’.

The spread of the legging legs trend was met with some anger and horror by other TikTok users, many of whom had already been through several cycles of similar trends and said they have had enough of social media being used to make women feel bad about their bodies.

“I had legging legs when I was anorexic and my body was shutting down on me, so I’ll skip this one thanks,” one TikTok user commented.

Another TikToker said, “Have we not learnt anything from the years and years of trauma that diet culture exposed us to as teenagers?”

Source: TND/TikTok/@Fl0rabutter/@ashleerosehartley/@maddy.nourishandlift/@notjassy 14

TikTok has taken some action by banning the term legging legs; if users in Australia search for the term on the platform, they will be met with a link to advice on eating disorders and a contact number for the Butterfly Foundation, a national support line for eating disorders and body image issues.

But searches for ‘#legginglegs’ or leggings legs remain unblocked, leading TikTok users to related clips with millions of views.

“TikTok is an inclusive and body-positive environment and we do not allow content that depicts, promotes, normalises or glorifies eating disorders,” a TikTok spokesperson told The New Daily.

“When people search for content related to eating disorders, they are shown a pop-up with information and a link to the Butterfly Foundation.”

Gemma Sharp, Monash University associate professor and senior clinical psychologist, said banning terminology generally does not remove the issue.

“People will find workarounds by changing the spelling,” she said.

“We should be promoting people of all body shapes and sizes wearing leggings and enjoying themselves.”

Dangers of body-focused trends

Ivanka Prichard, associate professor at Flinders University College of Nursing and Health Sciences, said the promotion of idealistic body shapes and sizes that might be unrealistic for the average person to achieve can lead to users making “unhealthy” comparisons.

“These types of social media trends have that potential to make young people think that this is how their bodies should look,” she said.

“When those trends are displaying a body type that’s really unhealthy or unnatural to achieve, then that’s not healthy for anyone to compare to, and can lead to people feeling dissatisfied about their shape and appearance in response to those coming comparisons.

“And we know that body dissatisfaction is one of the strongest predictors of eating disorders.”

Young people who are still developing their identity or feel more pressure to ‘fit in’ may be most vulnerable to the risks of body-orientated social media pressures.

Butterfly Foundation research found social media made 50 per cent of young people aged 12 to 18 feel dissatisfied with their body, and more than 70 per cent thought media and social media platforms needed to do more to help young people have a positive body image.

Women and girls on the alert for harmful messaging

But the day-to-day use of social media is also helping some users harden their defences against harmful body image and diet messaging.

Deakin University associate professor in sociology Kim Toffoletti said research she and colleagues conducted into young women’s use of social media for fitness purposes found girls aged 15 to 17 are aware much of the social media content they see can be harmful.

Instead of “narrow and stereotypical” imagery, young girls want more diverse body representation, and are looking for social media content that supports them in feeling good about their bodies and their wellbeing practices.

“When we talk about this kind of stuff, we often risk saying this is being imposed on girls … and that they have no agency to respond or reflect on it,” Toffoletti said.

“In fact, the girls that we studied are actually really switched on. They understand that the trends actually serve the purpose of the social media platforms – as well as fitness and wellness industries that are selling particular ideals.”

With awareness of the potential toxicity of social media body trends, the emergence of these trends can provide an opportunity for women and girls to discuss unrealistic and harmful body image pressures, as already seen in the backlash against legging legs.

Pressure on social media platforms to take action

Toffoletti said there needs to be more accountability from social media platforms around how their algorithms can promote harmful messaging.

This week, the heads of major social media companies such as Meta, Snap, TikTok faced an online child safety congressional hearing in the US that addressed allegations social media promoted everything from body image issues to child sex abuse.

At the hearing, Meta founder Mark Zuckerberg said: “The existing body of scientific work has not shown a causal link between using social media and young people having worse mental health.”

However, internal Meta research leaked by whistleblower Frances Haugen in 2021 found Instagram made body image issues worse for one in three girls.

Other social media platforms don’t do any better, with algorithms possibly reinforcing harmful mental health and body image issues.

Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences research found for people who are already diagnosed with an eating disorder, it is 4137 per cent more likely that the next video delivered to them by the TikTok algorithm will be eating disorder related.

It is also 322 per cent more likely the next video sent their way by TikTok’s algorithm will be diet orientated.

Toffoletti said moves by social media companies to ban certain terminology or promote access to mental health resources may be a case of helping to fix problems they keep causing.

“There really is no public accountability for the algorithm,” she said.

“We don’t see the back end of what they’re doing. That information is unavailable, so I do feel that what they are presenting is not the whole picture.”