Albert Einstein wrote a letter 72 years ago that showed his curiosity about birds and bees

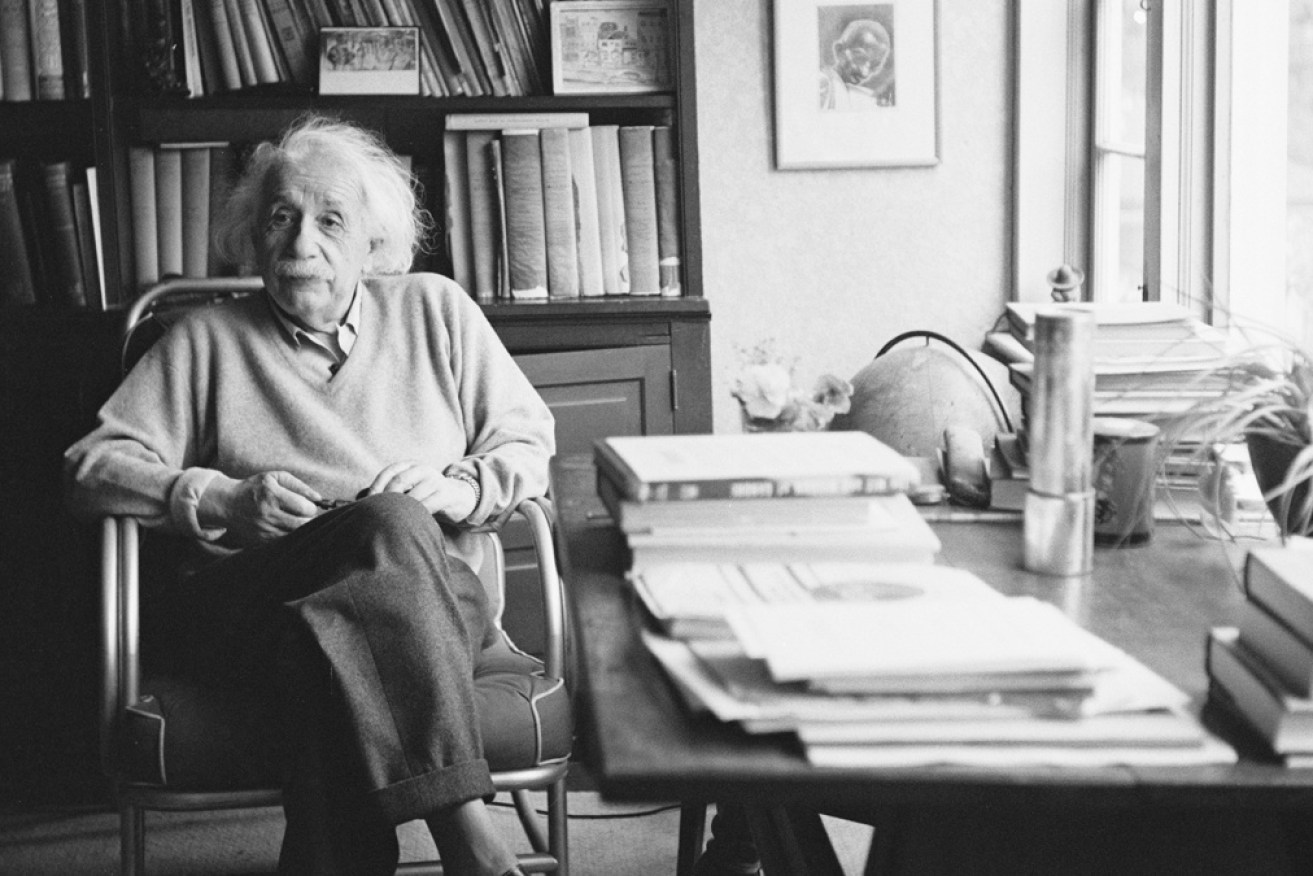

German-born physicist Albert Einstein in his study at Princeton University, where he met Karl von Frisch in 1949. Photo: Getty

Developing groundbreaking physics theories wasn’t the only thing on Albert Einstein’s mind.

It turns out he also had a keen interest in the birds and the bees.

In a previously unknown letter penned by the Nobel prize-winning physicist, Einstein considered whether new physics insights could come from studying how animals sense the world around them.

The short letter was addressed to Glyn Davys, an engineer with the Royal British Navy, in October 1949, and mentioned the prominent bee researcher Karl von Frisch.

Its content suggests that Einstein’s thought processes were ahead of his time, with research on animal sensory systems not emerging for another seven decades.

Albert Einstein’s letter to Glyn Davys touched on birds, bees, and Karl von Frisch. Photo: Dyer et al. 2021, J Comp Physiol A/The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

The letter, which was studied by a team led by RMIT researchers, was published this week in The Journal of Comparative Physiology A.

Adrian Dyer, a vision scientist at RMIT in Melbourne, said the letter demonstrated that Einstein was curious about science outside of physics and mathematics.

“One of the reasons I think Einstein is still so well known and prominent in today’s society is that he had a very multidisciplinary way of thinking about the world,” said Dr Dyer, who co-authored the paper on the letter.

Bees learn maths and a letter resurfaces

In 2019, Scarlett Howard, who studies bee cognition at Monash University in Melbourne, and colleagues published a series of papers demonstrating bees’ cognitive powers, such as their ability to grasp the concept of zero and solve simple maths problems.

Research has shown that honey bees can solve basic arithmetic and understand the concept of zero. Photo: Scarlett Howard

“If we showed them three blue dots, we trained them to add one, and if we showed them three yellow dots, then they needed to subtract one,” said Dr Howard, also a co-author of the paper.

“We basically taught them plus one and minus one.”

The research grabbed the spotlight in the media, but also caught the eye of Judith Davys, a widow living in the UK.

Ms Davys had read the researchers’ paper on bees’ mathematical problem-solving abilities, and reached out to Dr Dyer about a 72-year-old letter she had kept.

The letter, which was addressed to her late husband Mr Davys, was from none other than Einstein.

After verifying with the Albert Einstein Archives at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem that the letter was genuine, Dr Dyer and his team spent a year analysing it and piecing together what prompted Einstein to write it.

A lasting impression

The team suspected the letter was a reply to Mr Davys, who studied the use of radar to detect ships and aircraft, a top-secret research topic at the time.

To put the letter in context, the researchers dived into archives of news articles that had been published in England in 1949.

They found a news story that discussed von Frisch’s discovery that honey bees use polarised sunlight – which travels in one direction – to find their way around, a finding that eventually earned him a Nobel Prize in 1973.

German-Austrian ethologist Karl von Frisch made headlines in 1949 when he discovered that bees use polarised light to navigate. Photo: Getty

The story had been published in The Guardian newspaper in London in July 1949, which may have prompted Mr Davys to write to Einstein.

The team also discovered that Einstein had attended a lecture by von Frisch at Princeton University in April 1949.

The following day, Einstein and von Frisch met in private, and while there are no records of what the two scientists discussed, Einstein’s letter to Mr Davys offers a clue.

“I am well acquainted with Mr. v. Frisch’s admirable investigations,” Einstein wrote in his letter to Mr Davys.

Dr Dyer said the letter’s opening line suggested von Frisch’s bee discoveries had made an impression on Einstein.

“The fact that Einstein took the time to go and listen to von Frisch’s lecture, meet with him after and then respond to Davys later, means that he was very aware that to do good research, it’s good to look at other opportunities and other ways of thinking about the world,” Dr Dyer said.

The secrets of animal senses

In the letter, Einstein went on to discuss whether studying bees could help uncover new physics insights.

“But I cannot see a possibility to utilize those results in the investigation concerning the basis of physics,” Einstein wrote.

“Such could only be the case if a new kind of sensory perception, resp. of their stimuli, would be revealed through the behaviour of the bees.”

Andrew Greentree, a physicist at RMIT, said Einstein’s comments here reflected that the physics of the time could not explain sensory perception in animals.

For instance, concepts that we are now beginning to understand — such as the way dolphins and bats use sound as a navigation guide — were not understood then, said Professor Greentree, one of the paper’s co-authors.

But there is still more to learn about the connections between biology and physics.

“Biology is perhaps the ultimate proving ground for physics,” Professor Greentree said.

“Nature — using nothing more complicated than natural selection — has taken subtle effects and turned them into wondrous and practical features of the world around us.”

A scientist ahead of his time

The limited knowledge of animal sensing at the time didn’t stop Einstein from exploring the possibilities.

In just one sentence, Einstein proposed that studying animal behaviours could be the key to new discoveries, decades before scientists began unravelling how animals perceive their environment.

“It is thinkable that the investigation of the behaviour of migratory birds and carrier pigeons may someday lead to the understanding of some physical process which is not yet known,” Einstein wrote.

Indeed, research over the past decade has revealed how birds use the Earth’s magnetic field to help keep them on track while migrating over thousands of kilometres.

And one of the theories for birds’ magnetic-sensing capabilities is underpinned by ideas that Einstein proposed himself: quantum randomness and entanglement.

While Einstein dismissed these physics concepts as “spooky action at a distance”, research today shows he was actually onto something when it comes to how birds perceive magnetic fields.

Quantum randomness and entanglement suggests certain chemical reactions that occur in light-sensitive proteins in bird retinas are influenced by the Earth’s magnetic field, enabling birds to use it like a compass.

Professor Greentree said Einstein’s musings suggested he was broad-minded and willing to share his ideas with anyone who asked a question.

“He was open to new ideas about the origins of sensory perception, even if they might conflict with the physics that he himself helped to forge,” Professor Greentree said.

Dr Dyer said we could all learn something from Einstein’s letter.

“If elite-level researchers like Einstein were willing to look at information with very open eyes, then perhaps we should all have very open eyes for how we approach new solutions for the world,” Dr Dyer said.

–ABC