You would never allow a stranger to track your step-by-step location, read your text messages or view your photos, and yet many smartphone applications do just that.

As a new video illustrates, apps can access far more private data than we may ever realise.

The Danish Consumer Council has issued a warning very relevant to Australians, who are some of the world’s most prolific smartphone users.

[display-jwplayer playerwidth=”100%” playervideourl=”/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/The-Danish-Consumer-Council.mp4″]

• Avoid bill shock: how to spend less on phone data

• How consumers are at risk of email terror scam

• How you could end up paying the govt’s ‘spy tax’

Apps can request access, called ‘permissions’, to far more of our phones than they really need, including the names and phone numbers of friends and relatives. Sometimes this data is taken from the phone and stored at the headquarters of the company who built the app, where it can be used in marketing campaigns and be at risk of data theft.

Trend Micro consumer tech expert Tim Falinski says phone users can easily be duped by lengthy, complex sign-ups.

“Most users do not read the agreements and just blindly approve these, giving the app access to information they normally wouldn’t want it to have,” he says.

Unfortunately, these lengthy agreements are not going away, and it is far easier to simply accept and move on without considering privacy.

How to better protect your data

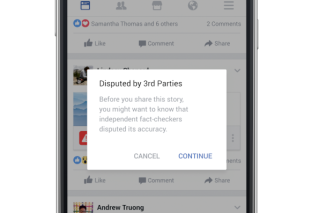

When it comes to app permissions, scepticism is healthy. Photo: Shutterstock

Appscore technical director Benny Sheering, an award-winning app developer, tells The New Daily that consumers need to read app descriptions carefully and sceptically.

“I see people installing apps and they tap yes to every permission request without actually reading what the app is requesting!”

An unusual request, like a weather app trying to access your phone contacts or photos, should be a warning sign.

“Think if the requested permissions actually suit the app,” Mr Sheering says. “Only grant permission to access anything you feel comfortable with sharing.”

Mr Falinski says so-called ‘free’ apps can be some of the worst offenders.

“How do people think all these apps are for free? They need to make money somehow and they do this in certain cases by using your personal information to allow targeted advertising or, worse still, sell off your information.”

Non-Apple users in the dark

It’s easy to forget what you’ve allowed an Android app to do. Photo: Shutterstock

Buuna CEO Paul Lin, a leading app developer, says those who don’t have iPhones need to be “more careful”.

This is because Apple apps must ask for permissions on a case-by-case basis, whereas operating systems like Android force the user to give up-front access to whatever the app requires.

“It may not be as obvious to the Android user why the app needs all those permissions at the time of downloading,” he says.

The biggest risk is a loss of privacy, not criminal activity, as all apps on the Apple and Google stores have been reviewed for scams and identity fraud.

“Users should always be aware of what the apps needs,” Mr Lin says. “Awareness isn’t panic though.”

“It’s more of a choice about what you want to share rather than anything serious or illegal.”