The superannuation changes we missed out on

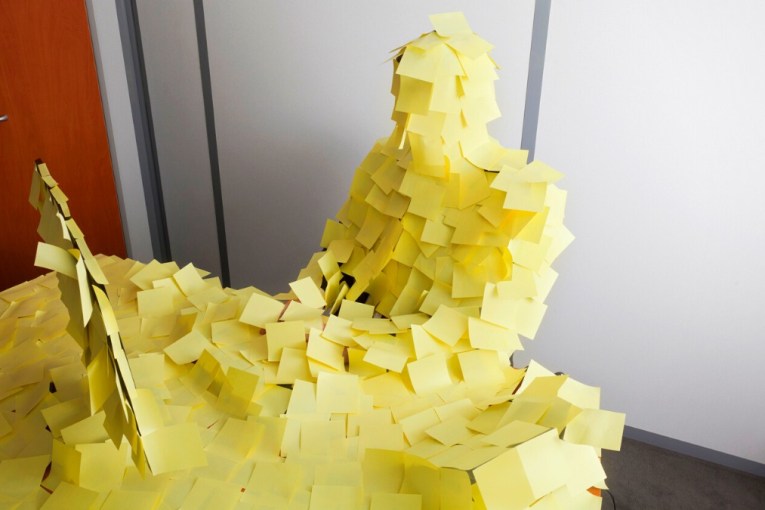

Waitresses and other female workers could have been given more help, experts say. Photo: AAP

The July 1 changes to superannuation missed several key reforms that would have helped workers save more for retirement, according to industry experts.

The industry has broadly welcomed the Coalition’s changes, which were aimed at making the system fairer.

But Eva Scheerlinck, CEO of the Australian Institute of Superannuation Trustees (AIST), which represents all non-profit super funds, said it was a missed opportunity to abolish the $450 threshold.

Currently, employers do not need to pay superannuation if an employee aged over 18 earns less than $450 in ordinary time earnings in any calendar month.

“The threshold impedes on the ability of people working multiple jobs to save for their retirement,” Ms Scheerlinck told The New Daily.

“We have examples where someone is working for three or four employers but they aren’t hitting the requirements for superannuation from any one of them.

“If we want superannuation to be truly universal then the threshold must go, particularly with the increasing casualisation of the workforce.”

The rule is not widely understood. A survey of 1059 employees by Longergen Research in 2016, commissioned by industry fund REST, found that 47 per cent of casuals and 40 per cent of part-timers thought they were paid super from the first dollar they earned.

An estimated 220,000 Australian women and 145,000 men are missing out on about $125 million of super a year because of the rule, according to the Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia (ASFA), which represents the entire industry.

“Removal of the threshold is a long overdue correction,” ASFA chief executive Dr Martin Fahy said.

The workers hardest hit by the threshold are in retail, hospitality and nursing, and are overwhelmingly female.

ASFA has estimated that a 19-year-old student working part-time for five years and earning $4000 a year would miss out on $1900 of super.

For a woman aged 37 working part-time and earning $5000 a year, the loss would be $1425 over three years, ASFA found.

The threshold is a relic from when compulsory super was first legislated in 1992. It was aimed at placating small business owners who were worried about the administrative costs of keeping track of small amounts of super.

The $450-a-month threshold is based on $5200 a year, which was the tax-free threshold in 1992.

Also, missed opportunity to increase SG

AIST and ASFA both said the July 1 changes could also have sped up the rate of increase to the 9.5 per cent superannuation guarantee (SG).

Employers currently must pay an extra 9.5 per cent of a worker’s wages into their super fund. Because of a Coalition government amendment, the levy won’t increase until 2021.

Labor had legislated for it to steadily rise to 12 per cent by 2019. The Coalition plan will instead have it reach 12 per cent six years later, in 2025.

Superannuation is a levy, which means the cost of the eventual rise should be borne by employers, and not reduce workers’ take home pay – unless employers cut pay to offset the increase.

AIST’s Ms Scheerlinck said 9.5 per cent was “simply not enough”.

The lobby group has estimated that an average wage earner receiving super at 9.5 per cent for their entire working life will retire with around $300,000, in today’s dollars. That would increase to $400,000 if the superannuation guarantee was increased to 12 per cent.

“Australians are living longer in retirement so it is more important than ever to go to 12 per cent,” Ms Scheerlinck said.

ASFA’s spokesperson agreed: “Lifting the rate is important for sustaining the super system and ASFA will continue to advocate for this fundamental improvement for the system.”

ASFA also said it would have given more powers and funding to the Australian Taxation Office to tackle the widespread problem of unpaid super.