This is who should benefit most from Morrison’s budget

The Coalition was busy over the weekend drawing sharp lines between itself and Labor on what it calls the ‘housing tax’, Labor’s desire to ‘put up income tax’ and introduce an ‘electricity tax’.

Those tags refer, respectively, to Labor’s plan to ban negative gearing on established homes after next July, its lack of a policy (so far) to address the tax increase known as ‘bracket creep’, and its plan to introduce a ‘baseline and credit’ trading system in the electricity generation sector.

• Budget 2016: nation building with a fistful of dollars

• ‘Budget will target high-income earners’: Morrison

• Kidman deal ‘contrary to national interest’

• Tycoon has 55 homes: you pay for negative gearing

So Labor’s for more taxes and the Coalition’s for less?

Well no. Treasurer Scott Morrison will increase the taxes paid on superannuation by wealthy Australians, increase the taxes paid by multinational corporations, and likely increase the excise on tobacco.

We won’t know until Tuesday’s budget how Mr Morrison’s alterations will shift the tax burden within socio-economic groups. Inevitably some groups will pay more than previously – the question is which ones.

Mr Morrison has stated several times that the overall tax burden, usually expressed as a percentage of GDP, will not change.

Treasurer Scott Morrison says the overall tax burden will not rise. Photo: AAP

To achieve that, he’s doing a lot of juggling. He wants to increase schools funding, but won’t match Labor’s level of funding for the Gonski reforms.

And spending splurges such as the $50 billion plan to build 12 submarines in South Australia will have to be clawed back in other areas. Family tax benefit is one possible area he could target.

This year is different

So how are we to judge this budget’s economic credentials?

First, some context. This year is far from a normal year, because this budget will effect Australia’s annus horribilis – 2017.

That is the year in which economist Ross Garnaut has pointed out, “the fall in business investment from the end of the resources boom has a long way to go”.

It’s the year in which a surge of private-debt-funded consumption, which has been holding up the employment numbers, will start to run out of puff.

And it’s the year in which the currently anaemic inflation rate threatens to edge further towards deflation. Managed badly, it could be a very bad year.

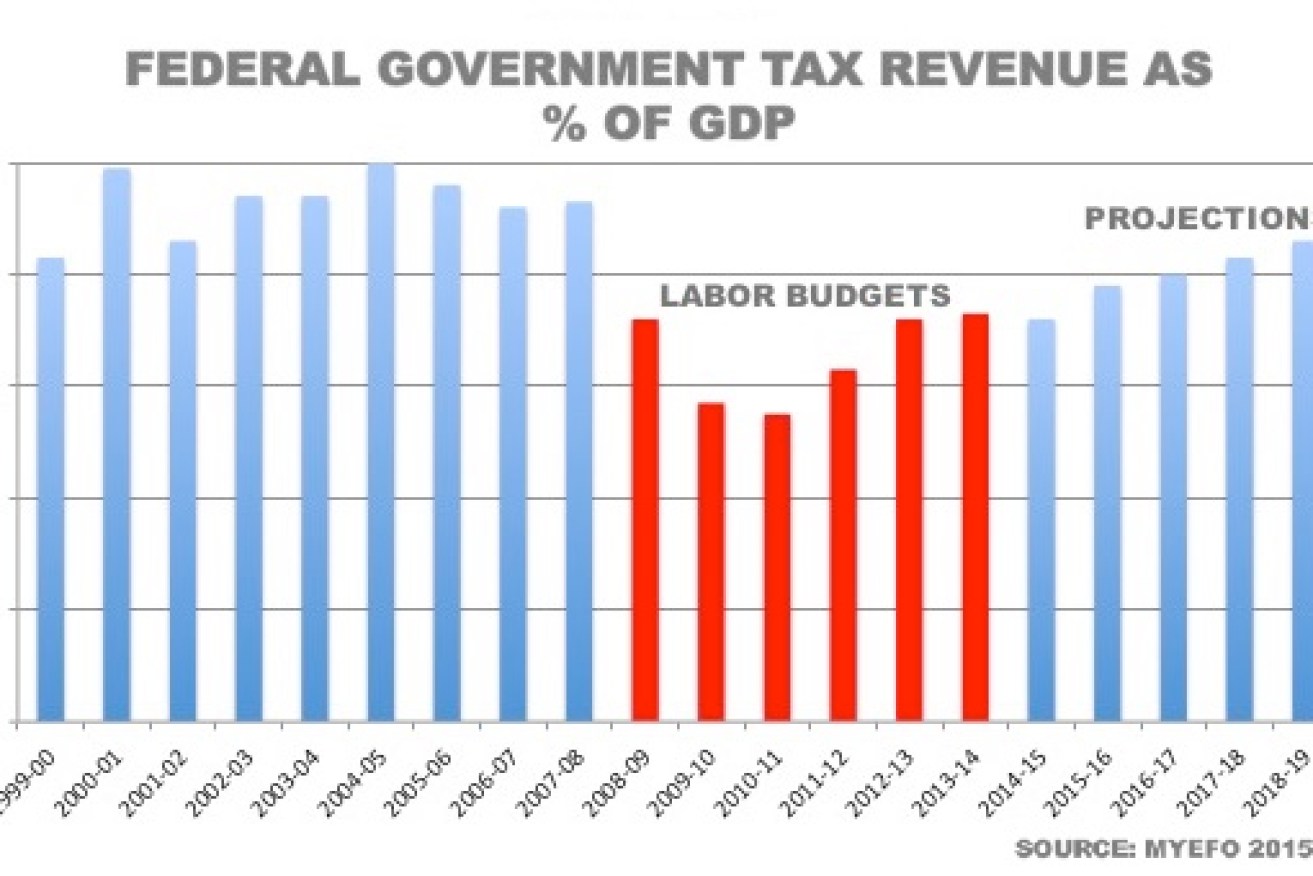

Against that backdrop, vowing to stop the revenue side of the budget rising looks reckless. As the chart below shows, tax revenues are recovering from their GFC lows, not helped by the terms-of-trade slump seen since late 2011.

Whether Mr Morrison actually means the overall tax burden won’t rise is yet to be seen – he may well plan to allow it to rise back to levels last seen under the Howard government.

If he does, it will be in defiance of the neo-liberal forces at work within his own party and the commentariat – forces that have been very vocal ahead of budget day.

Tony Abbott, who as PM decided that a weakening economy was best served by the 2014 austerity budget, has vowed to be a standard bearer for this disgruntled right-wing and use his high profile to “get attention”.

We’ve had Victorian Liberal powerbroker Michael Kroger accusing the Grattan Institute of being biased toward Labor – yep, the think tank set up jointly by Peter Costello and Steve Bracks – for supporting the push to recover revenue via negative gearing and capital gains tax reform.

And on the ABC’s Insiders programme on Sunday, Financial Review editor Michael Stuchbury railed against the “poison pill of spending from the previous Labor governments” that was “totally unaffordable”.

Voices such as these work hard to make the small government view synonymous with ‘economic growth’.

Peter Costello and John Howard saw tax revenue surge. Photo: AAP

Increasing tax revenue, borrowing to help smooth the economy’s transition away from the mining boom, and increasing spending to maintain world-class health and education are derided, as if those are the things that will send the economy backwards.

Moral vs economic argument

Those views are part of a long-running moral argument made by the right – that ‘my money’ is sacred, and that every dollar stolen by the greedy, bloated government is a ‘waste’.

Millions of voters do not see it that way. In 2013, Barnaby Joyce rather foolishly asked a TV audience “hands up who wants to pay more tax”, only to see a large cross-section of the audience put their hands up – not to support ‘waste’ but to support investment in public services.

The problem we face this year is that if moral arguments, dressed up as economic arguments, hold sway, the resulting budget would threaten economic growth in 2017.

This is not the time for bellicose ideologues to claw back more of ‘their money’. In the good times, let’s have that fight – but not as we march into the economic gully of 2017.

The budget on Tuesday must be judged on pragmatic economic criteria.

Is it protecting jobs? Is it assisting industries and businesses to stay on their feet through the slump? Is it continuing to educate and protect the health of tomorrow’s workforce?

If the answers are mostly positive, Mr Morrison may have hell to pay on the right of his party. But Australia will be the richer for it.