Alan Kohler: The optimists have failed us. Pessimists, please report for duty

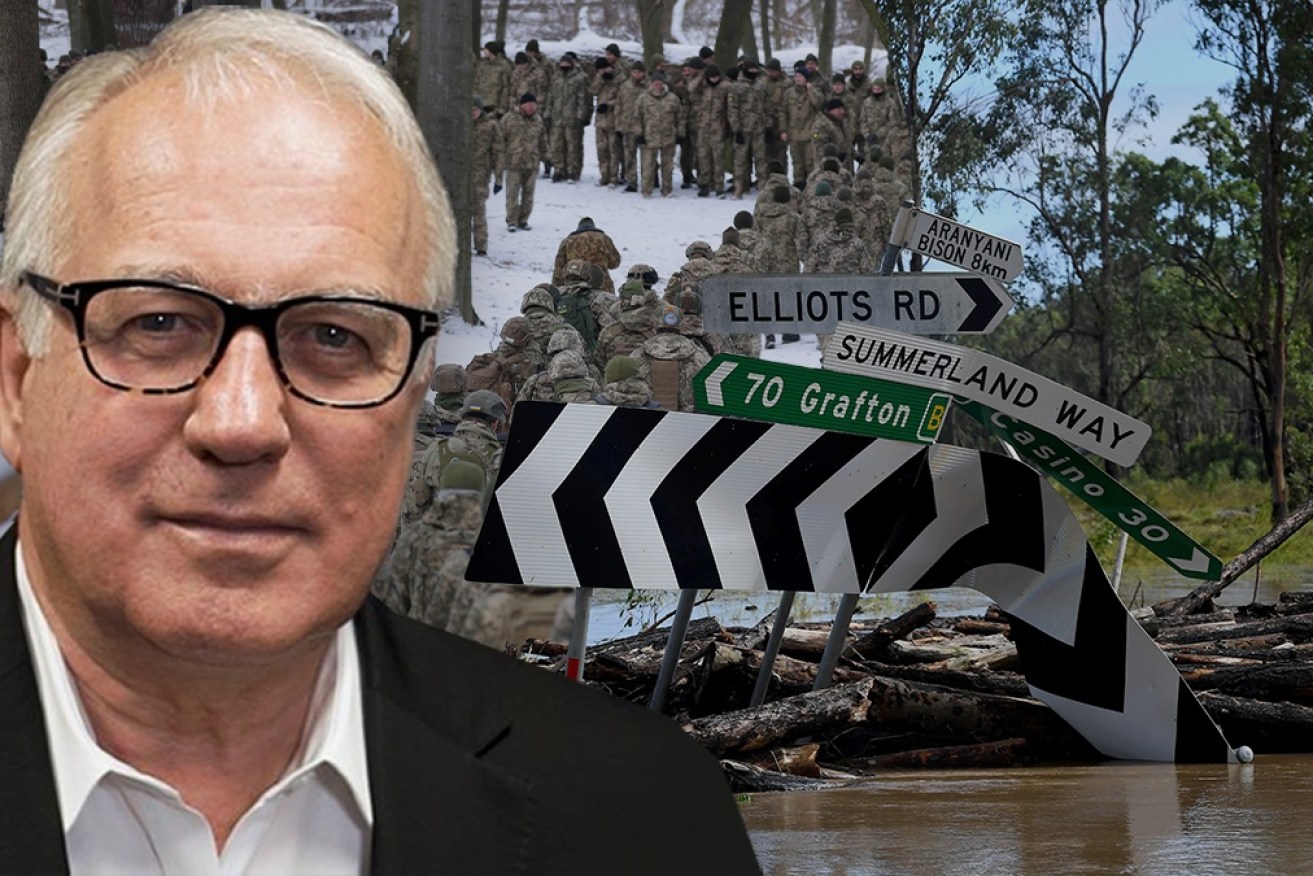

COVID, climate change and war in Europe could have used a pessimist to plan for them. Photo: TND/Getty

The main problem we have as a society is that all of our leaders – politicians and executives – are optimists one and all, not a pessimist among them.

It goes with the job. You can’t be a leader unless you’re an optimist because you must persuade those around you that not only will everything turn out great, but also that only you can make it so.

A gloomy doomsayer would never be elected to high office or get appointed to run a company: The shareholders and voters wouldn’t believe they could improve their lot.

Preparing for the worst

But while optimists make good leaders in good times, they don’t prepare for the worst because they think the worst won’t happen – I know because I am one, to whom the worst has sometimes happened, always unexpectedly.

So it makes sense that nothing has ever been done about climate change, either to prevent it or protect us from its effects, even though scientists have been seriously warning about it since 1990, because politicians and CEOs are inherently inclined to think it’s going to be OK. It’s almost impossible for them to think otherwise.

And when scientists were warning after the SARS outbreak that there would soon be a much worse pandemic, nothing was done, and even when there really was a much worse pandemic in 2020, Australia’s leaders didn’t bother with vaccines because, well, it’ll be OK, and the US President at the time, Donald Trump, actually said: “It’ll all just go away, like magic, you’ll see”.

It’s also why the world has been so shocked by Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

How could an optimist predict that a significant nation in the modern world, a member of the UN Security Council no less, would attack a neighbouring country unprovoked, and kill its unarmed citizens?

For most western politicians, none of whom were alive when Hitler’s Germany marched into the Rhineland, invaded Czechoslovakia and murdered six million Jews, the invasion of Ukraine was unthinkable right up until the moment it happened at 4am on February 24.

Now everything is turning out very badly on many fronts, and pessimists must report for duty. Better late than never.

Pessimists desperately needed

Global warming is well under way no matter what cuts to emissions are achieved from here, and the cuts that are grudgingly eked out by the optimists who lead us will be vastly insufficient to prevent further disaster.

We desperately need some pessimists leading the response to climate change, otherwise we’re doomed.

At least with the plague, gloomy scientists have done a magnificent job inventing vaccines and treatments that might actually protect us from the next COVID variant.

Without that, the optimists in charge would have us maskless and dancing in crowds, failing to help get Africa vaccinated, sitting ducks for the next virus.

Meanwhile, global geopolitics have changed irrevocably, and can no longer be relied upon to turn out for the best, in the best of all possible worlds, to quote Dr Pangloss in Voltaire’s Candide.

For 80 years, rich countries with well-resourced militaries have only attacked smaller countries far away, like Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq (and have usually lost through an excess of optimism, but that’s another story).

Russia’s merciless, unprovoked attack on a European country, Ukraine, and the economic war now being waged against Russia in response change everything.

The US dollar was placed at the centre of the global financial system at Bretton Woods in 1944 and, as a result, the post-war settlement gave America the valuable franchise of owning the world’s reserve currency.

Dollar weaponised

Seventy eight years later, the US dollar has been weaponised in defence of Ukraine, and there will be no going back to civilian life for the greenback.

The world’s dictators have always had a love/hate relationship with the US dollar – wanting to ensure their own plunder is safely stored in the them, preferably in a Swiss bank, while chafing at the power it gave America.

Now they know it can be used against them, and for that matter, so can their trusted banks, now that Switzerland has agreed to freeze Russian assets – including Putin’s – in solidarity with Ukraine.

We are now heading into a bipolar world, and how complete that division ends up being will depend on whether China decides to fully support Putin, and really does want to retake Taiwan.

If it does, it now knows it will have to completely leave the US dollar system, and require no American currency.

Putin’s response

As for Russia, it is now engaged in two ferocious wars at once, the one in Ukraine against 44 million very determined, very angry Ukrainians, and the economic one against the West.

And in the second of those it would be wrong to think Russia is powerless. It is not just about gas to Europe, of which 40 per cent comes from Russia, or even Russia’s 12 per cent of the world’s oil output.

Putin also has the means to cut off critical minerals and gases needed to sustain the West’s supply chain for semiconductor chips, in the midst of a worldwide chip shortage.

He could seriously damage the aerospace and armaments industry in the US and Europe by restricting titanium, palladium and other metals. The nickel price has already gone vertical.

On top of that, Ukraine is described as the breadbasket of the world because of all the wheat it grows, so if Putin gets control of that he could choke off a lot of the world’s food supplies as well. The price of wheat has already gone well above the level that sparked the Arab Spring uprisings in 2011.

So with critical supplies of food, energy and metals under its control, Moscow could release an inflation shock as violent and devastating as the first oil crisis in 1973, with a recession and bear market to match.

And that’s leaving aside the fact that it owns 5977 nuclear warheads, presumably aimed at European and American cities.

Pessimists have been worrying about this since Jonathan Schell published The Fate of the Earth in 1982, about the consequences of a nuclear war.

It may be time for the optimists in charge to download a copy of that book, as well as Fiona Venn’s book, The Oil Crisis, and David Wallace-Wells’ analysis of climate change, The Uninhabitable Earth.

There is some grim homework to catch up on.

Alan Kohler writes twice a week for The New Daily. He is also editor in chief of Eureka Report and finance presenter on ABC news