Glenn Stevens has exposed the great Australian delusion

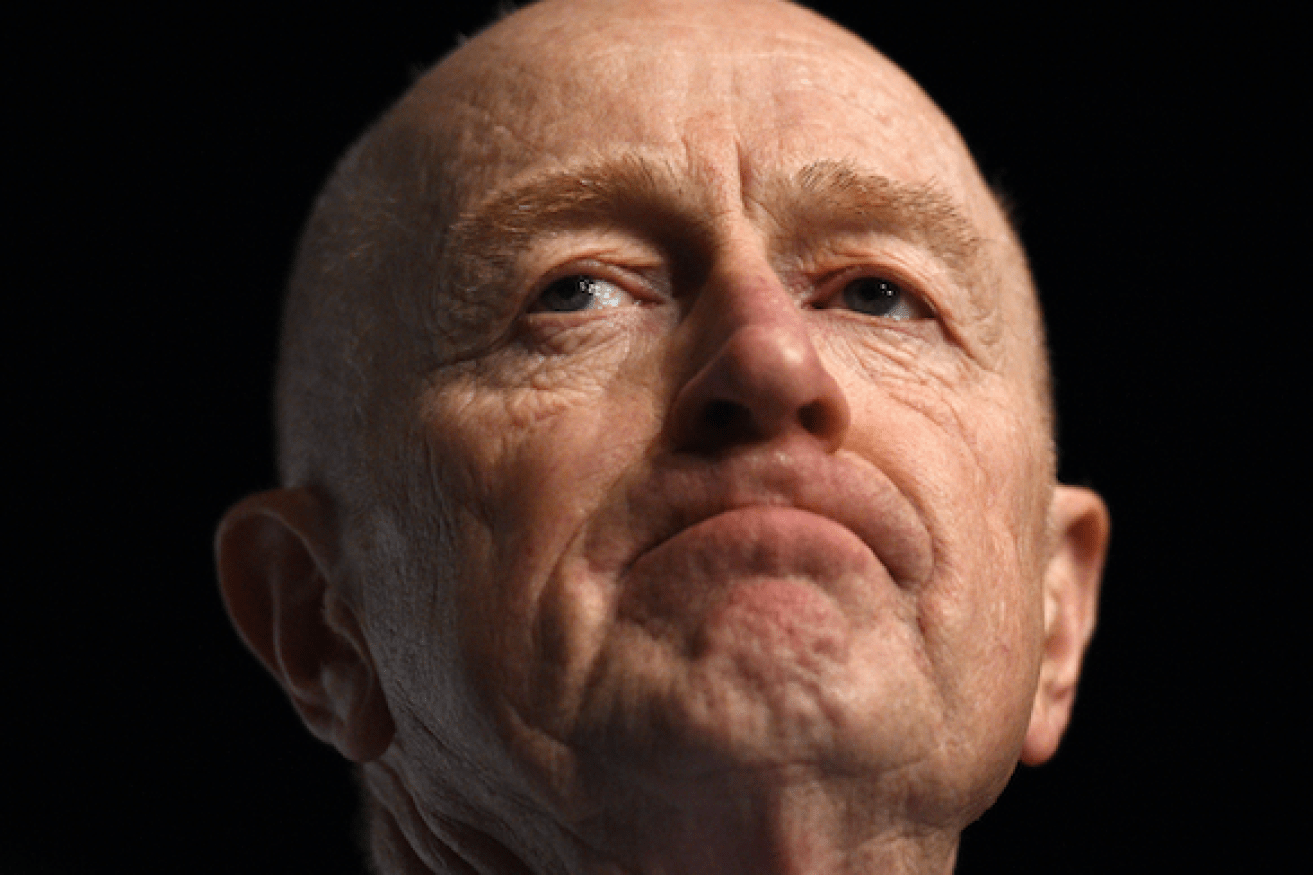

The RBA boss was outspoken in his final speech. Photo: AAP

ANALYSIS

It’s a pity that the news media was awash with Olympic headlines when Glenn Stevens gave his final speech as governor of the Reserve Bank on Wednesday.

At a more quiet time of year, more Australians would have heard one of our top public officials exposing the Great Australian Delusion.

He didn’t use those words – they are mine – but he was more outspoken than ever about the rot at the heart of our economy.

While the nation wasted years obsessing over public ‘debt and deficit’, we should have been paying attention to the towering edifice of private debt in the housing market.

It was a remarkably honest speech from a man whose mandate, as head of our central bank, has been simply to keep inflation between 2 and 3 per cent, and the jobs number as close to full employment as possible.

Click here to read the key passage of Glenn Stevens’ speech

Importantly, he argued:

Glenn Stevens says our private debt is a much bigger concern than we think. Photo: AAP

– public debt can be a good thing if used to create assets that produce long-term economic returns for taxpayers, and generally a bad thing if used to finance a government’s recurrent spending;

– public debt is on a trajectory to become too large, but is still less than a third of Australia’s stock of private debt;

– loose monetary policy is failing to stimulate demand because Australia’s households are over-indebted;

– and national debate has wrongly focused on public debt, when the private debt problem has long been clear to observers from overseas.

A skewed debate

Mr Stevens correctly observed that: “… popular debate in Australia about government debt and how we limit or reduce it seems so often to be conducted while largely ignoring the size of private debt.”

This blindspot is not getting any better.

The size of our key mortgage lenders, and their extraordinary profits, are still being welcomed by some as “good for everyone“.

News Corp columnist Terry McCrann, for instance, defended the Commonwealth Bank’s record profit of $9.5 billion this week by supporting the big four CEOs who “have been trying to explain how a bank has to balance the interests of all its stakeholders.

Commonwealth Bank boss Ian Narev has announced a record profit. Photo: AAP

“Much of the media seem to think that the only people that interface with a bank are those borrowing money to buy property.

“In fact there are also those who deposit money with banks – without which, it should be blindingly obvious, the bank would have no money to lend to those home buyers.”

McCrann has correctly identified how Australian banks work.

The problem, however, is that money-go-round has little to do with how a productive, sustainable economy works.

Banks take the economic surplus generated by households and businesses, and lend it to other households and businesses, taking a cut of the interest payments on the way through.

But banks are not the only place that surplus can go – it can be spent on job-creating consumption, invested in productive businesses, used to buy government or corporate bonds, or invested abroad.

A disastrous reform

Former PM John Howard changed capital gains tax laws. Photo: AAP

The problem is, ever since key reforms by the Howard government, banks have found it vastly more profitable to lend money to households than to businesses.

And here’s the rub. Banks don’t continue lending money to a business unless they see a corresponding rise in the value of what the business produces.

Yet banks have continued to lend into the household sector well ahead of wages growth – hence our world-beating levels of private debt.

As the chart below shows, back in 1990, banks lent a lot more money to businesses than to households.

However, when the Howard government introduced its capital gains tax discount in late 1999, it combined with the existing negative gearing laws to make property investments more attractive than they’d ever been – because now they were subsidised through large tax rebates.

As Malcolm Turnbull himself noted in the early years of this market distortion, it “encourages people to invest in a manner which turns income into capital and, as in the case of negative gearing, allows them to deduct income losses at, say, 48.5 per cent, and then realise gains and pay tax at effectively half that rate”.

The banks have been encouraged to invest more in housing than ever before. Photo: AAP

Put another way, the tax system has pumped money into the housing market at the expense of business lending. That is not “good for everyone” – just for some.

It has turned the banks into something akin to a Chinese government-sponsored enterprise – able to grow in size because of a central-planning decision that creates an artificially expanded market for their services.

Poor old Mr Stevens has had to manage the Reserve Bank through 10 of the 17 years since those disastrous policy decisions were made.

The Great Australian Delusion is that a healthy economy is supposed to work this way.

Mr Stevens knows that’s not true. And despite all noise of the Olympics, had the decency to say so.

Let’s hope a few people heard him.