If there’s another GFC, Australia will feel it

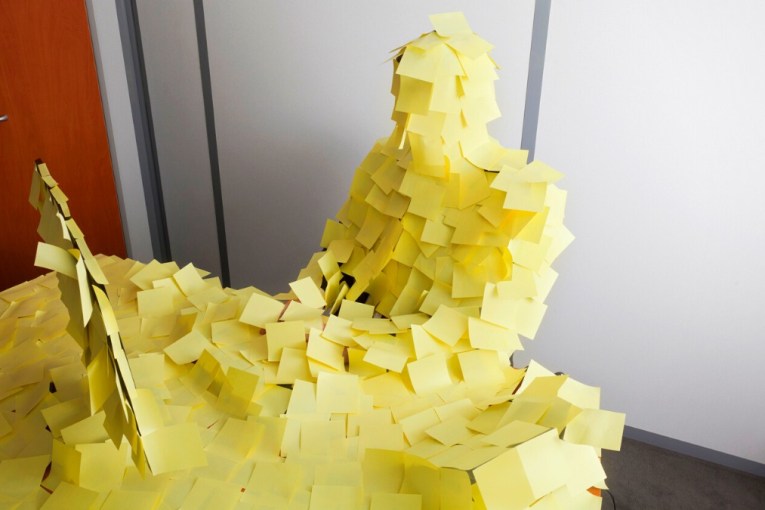

Getty

Last week US billionaire hedge fund manager George Soros made an alarming statement.

The world’s economy, he told a forum in Sri Lanka, is beginning to look like it did in 2008, just before the global financial crisis hit.

The comments came as the Chinese stock market was plummeting to dramatic new lows, followed by pretty much every other major stock market around the world, including Australia’s ASX.

• Rob Burgess: A slide in house prices will be good for the economy

• Aussie shares lose $33b after second Chinese market slump

• The tide is falling on some of our biggest assets

Whether or not Mr Soros is right remains to be seen – and it’s worth noting that most commentators are not quite as pessimistic as he is.

But Mr Soros has an excellent track record at predicting crises. As a hedge fund manager, he profits from taking ‘short’ positions in markets he thinks are about to crash. And as his billions testify, he is very good at it.

Accomplished hedge fund manager George Soros warns markets could be in for a difficult time. Photo: Getty

If he is correct, and there is another GFC around the corner, one thing is certain: this time Australia will not be spared the pain like it was in 2008.

Why not? Because any such crisis will almost certainly be caused by China, and where China goes, Australia follows.

Australia’s dangerous reliance on China

According to the Australian Trade Commission, Australian exports to China account for 33 per cent of our total exports (as of January 2015), and twice as much as the number two, Japan. At that time, iron ore accounted for close to 60 per cent of exports to China.

Coal, Australia’s other great export, and one that is looking in even worse shape than iron ore, accounted for 12 per cent of exports to China.

In other words, the importance of selling iron ore and coal to China simply cannot be overstated.

From 2008 onwards, while the rest of the developed world suffered recession, high unemployment, wage stagnation, cuts to public services and a radically falling quality of life, Australia continued to prosper precisely because of this reliance on China.

The Asian powerhouse was buying Australia’s iron ore in absurd volumes, at absurd prices, to fuel its feverish development. At the peak of the mining investment boom, iron ore was being sold for $US180 a ton.

As of Friday, the iron ore price was a paltry $US42 a ton.

A volatile stock market

China’s stock market is immature, and Chinese investors are highly unsophisticated, pouring money into stocks without looking at whether they are a good investment (a bit like Aussies and property, some might say). The result was a stock market bubble, which has so far burst twice: once in mid-2015, and once last week.

The Chinese government’s clumsy attempts to intervene have probably made things worse. Hopefully this is just a learning curve, and not something more serious. The trouble is it could be something more serious – no one really knows at this point.

The Chinese stock market experienced a halt last Thursday and rebounded the next day. Photo: Getty

So, how relevant is all this drama to Australia’s exports to China? Directly, the answer is probably “not very”. It is the companies listed on the stock exchange, and the individuals and institutions that invest in them, that suffer directly from these market crashes. And the companies on the Chinese stock exchange make up a relatively small fraction of the Chinese economy.

But according to John-Paul Smith of Ecstrat, falling share markets combined with a rapid devaluation of the Chinese currency could result in ‘capital flight’ out of China – which is to say, investors taking their money out of China and investing in markets that look more promising, such as the US.

In short, this would mean that China would have less money with which to invest in its own growth. And this vicious circle would be bad news for Australia.

The dollar value of exports to China is already rapidly declining from its peak in 2013. And that’s just in a business-as-usual scenario, where Chinese growth slows at a moderate, manageable rate.

If China were to enter a serious crisis, the effects on Australia could be devastating.