Michael Pascoe: Beware unintended consequences of housing reform

housing. Photo: Getty/TND

If you think big picture housing reform is difficult – and it certainly is –wait until you get into the detail.

That’s where the Law of Unintended Consequences works particularly hard, where much of the sweeping blanket planning reforms loved by developers and their shills hit the rocks.

For all that our major cities need densification and greater varieties of housing, the dictated top-down, one-size-fits-all mega reform as proposed by the New South Wales government is in danger of creating more problems than it solves – including less housing rather than more in the short term.

A landmark Urban Design Association submission on the intended effects of NSW’s proposed low and mid-rise housing reforms is alight with red flags for the “simple answer” beloved by politicians and developers for a mixture of complex problems.

This is by no means a NIMBYs v YIMBYs matter. It’s about increasing density and achieving more housing supply in a way that makes a city better to live in, rather than worse.

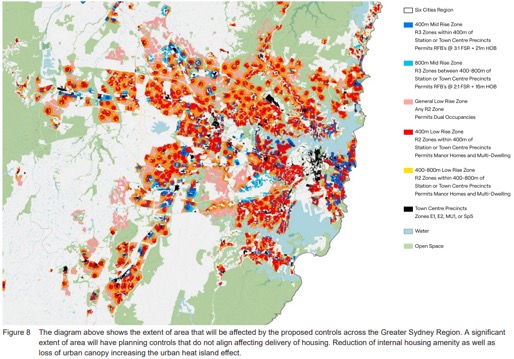

There is not the space here to do the Urban Design Association submission justice – download it from its site – when the government’s planning reform stands to impact up to 70 per cent of all the land that currently allows residential development across NSW’s ‘Six Cities Region’.

That’s a lot to throw over to “the market” when planning controls do not align, causing loss of amenity.

“The UDA acknowledge the need for densification, but believe that the proposed blanket controls need further refinement based on detailed lot testing to ensure that controls are fit for purpose and can deal with the variety of lots sizes and shapes, block depths, street widths, and plant ecologies that span this vast area,” states the submission.

That’s the sort of thinking that the development industry complains about, why it had the newly elected NSW government immediately scrap the Greater Cities Commission.

Among the dangers of “letting it rip” identified by the UDA:

- Increasing viability of short-term housing delivery. There is a risk that the vast but dispersed nature of the development incentive, with approved projects all competing for construction labour and resources, will not deliver a large net increase in housing quickly. Indeed, there is the risk that in the short term, leaving vacant or demolishing perfectly habitable existing housing could reduce the net dwellings available in areas

- Retaining existing, well-located affordable housing. When older, modest dwellings with lower rents are replaced by new, more expensive dwellings, the very people this policy is seeking to help are priced out of the area. Older walk-up apartment buildings provide good housing near many centres. Any policy needs to address the unintended consequence of turbocharging gentrification in desirable areas

- Aligning housing growth with community infrastructure. Community services, schools and open space are finite resources. Any area can take only so much population increase without requiring more public services. Higher-density living will require new types of public spaces and recreation facilities previously not needed by families in areas with private gardens. How this change is monitored and new investment prioritised should be addressed to sustain the strategy of higher-density cities

- Fostering thoughtful change that values older urbanism that already works. NSW is fortunate to have many older neighbourhoods with intrinsic qualities that can no longer be produced by modern urbanisation. Many areas are already models of higher-density living with sustainable travel behaviours. With stewardship from councils and careful attention to redevelopments and adaptive reuse, these areas are offering a diversity of housing in relation to age of stock, tenure and form while retaining their appeal to generation after generation. With the land area of metropolitan NSW, Sydney Metro switching on housing opportunities and fabulous new planned centres like Bradfield in the pipeline, a policy that undermines the heritage protections of these areas is not justified.

The low and mid-rise proposals are part of a suite of planning reforms including blanket medium and high-rise approvals around key rail and metro stations and town centres with extra height and floor-space-ratio allowances for building that include affordable housing.

If all stations and town centres are included, most of Sydney is up for development grabs irrespective of suitability.

“While in some locations additional housing could be appropriate, in others it could be totally inappropriate,” the UDA warns.

“This risks widespread community backlash and the possibility that less, not more housing will be delivered over the next few years.”

An example of complexity of the real world is the government’s blanket “walking distance” ruling around stations – it ignores the real walking distance if there are barriers created by major roads and waterways, how hilly the terrain is, and whether the stations have frequent services and are linked to a centre with facilities.

Just because a train station exists, it does not mean there is other key infrastructure necessary for successful densification, such as an effective road structure, shops, schools and open spaces.

“Upzoned single detached, low-density housing is easiest to redevelop and therefore likely to develop first, typically increasing density on the outer edge of the 800m walking distance which will increase traffic further away from the centre,” the submission observes.

Part of the appeal of densification for the government and developers is the idea that adding more dwellings in an existing residential area saves on the need to provide supportive infrastructure, but greater population still requires extra infrastructure, whether it’s more schools or open spaces where previously there were large backyards.

“The short term ‘urban consolidation = no new public investment’ theory seems unlikely to satisfy communities experiencing real life, localised examples of under-provision.”

And then there’s the problem of the reforms resulting in fewer dwellings.

“There is a possibility that the proposed controls will result in the demolition of perfectly habitable, modest older housing to be replaced by more expensive dwellings with smaller households, i.e. gentrification and a reduction in overall population density,” says the submission.

The current experience of inner-city Potts Point shows it is not just a “possibility” – blocks of smaller, cheaper flats replaced by bigger, much more expensive units.

The quality outcome is impossible to blanket legislate. Among its recommendations, the UDA says councils should be involved in informing new development controls for their area.

“Councils are the best placed to help shape and lead growth within their local government areas, understanding the community’s needs, unique characteristics and constraints that are essential to deliver place-based solutions.”

The Minns government steamrolling councils is already causing a backlash. A conversation with the former mayor of a high-density part of Sydney pointed to the success of an earlier method of increasing housing: Setting targets for each LGA and leaving it to the local council to work out the best way of achieving it.

The mayor noted only two councils failed to meet their targets and thus required state intervention.

But that’s not what the developer lobby likes.