Try not to get too excited, but there is finally something positive to report on the housing front.

Alas, there’s not a government committing to the real reforms needed to deal with our housing crisis – the major parties are still hoping to a greater or lesser degree that “the market” will somehow solve the problem for them (the Liberal Party is actually looking to exacerbate the housing inequality gap), and housing is continuing to become more expensive to buy or rent.

No, the good news is that the period of crazy housing construction cost inflation is over. That has implications for interest rates and dragging housing starts off the floor.

It won’t make housing cheaper, but as we adjust to construction prices being what they are, it will help allow more homes to be built, though still nowhere near enough.

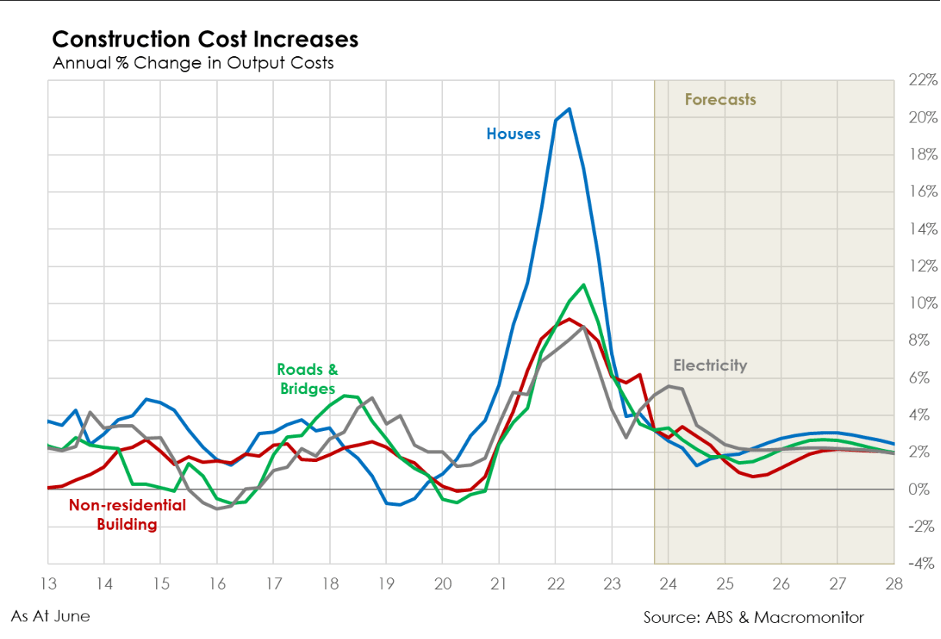

Construction industry research and forecasting company, Macromonitor, scores both housing and non-residential building cost increases normalising, the annual construction cost index falling to an estimated 3.2 per cent at the end of this quarter with housing construction inflation on its way to 2 per cent for the financial year and just 1.7 per cent next financial year.

All construction costs blew out during the epidemic with global supply chain problems and labour shortages, but the graph demonstrates the particularly disastrous impact of dud Morrison government policy on housing construction.

Instead of taking the advice of most independent economists to controllably invest in public housing as Covid hit, Treasury came up with HomeBuilder – throwing more than $2.5 billion at people who mostly did not need it for renovations and new buildings, exacerbating the aforementioned supply chain and labour problems, contributing to overall inflation jumping and the RBA’s subsequent interest rate hikes.

HomeBuilder was launched in June 2020 as an uncapped, demand-driven (i.e. stupid) stimulus expected to result in 27,000 applications worth a total of $688 million.

Some 138,101 applications later, housing construction costs were pushed through the roof, so to speak. Some of the early grants helped get relatively inexpensive homes over the line, some of them provided gold-plating for $700,000 renovations.

The total scheme should serve as a government administration case study of what not to do – a chapter in the review we’re unfortunately not having of Treasury’s competence.

While some individuals enjoyed a $25,000 gift from the taxpayer, the public has been left with no asset to show for its investment – unlike the same money being spent on public housing – and everyone suffering from the excessive inflationary impact. And then there are the many builders who have been sent broke when caught between fixed-price contracts and much higher costs.

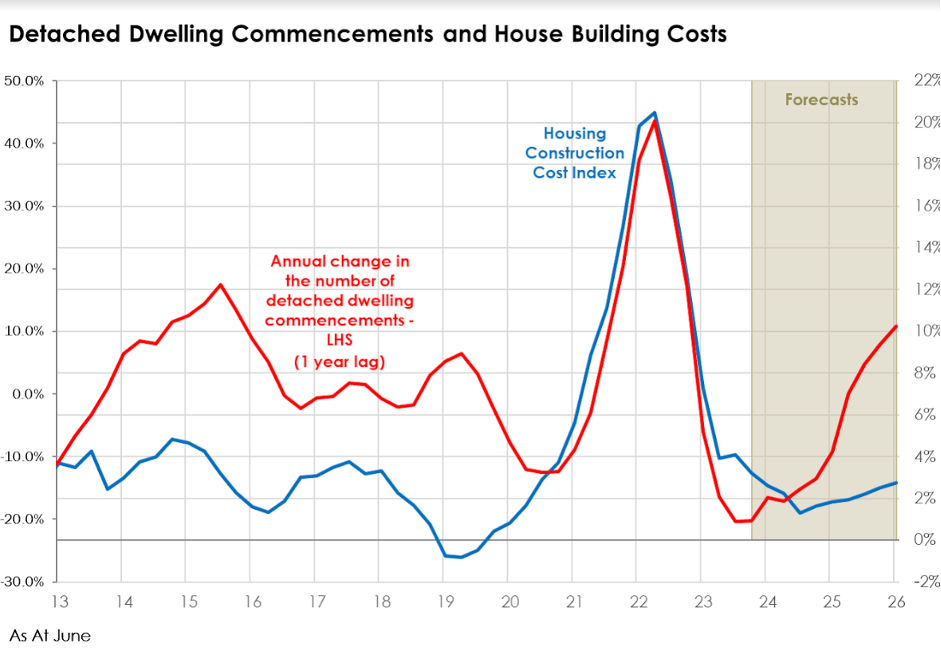

Four years later, the impact is finally washing out of the system, which Macromonitor expects will help detached dwelling commencements climb out of the hole they are in.

Macromonitor economist Natalie Senga says that hole has a pass-through effect on costs as the construction pipeline shrinks.

As commencements rise, driven by population growth, Macromonitor expects construction inflation to remain around its pre-Covid average, something that will allow for greater stability in the construction industry.

This is just the construction cost element – important in measuring inflation and a factor in overall housing costs, but not the main game of our imbalance of supply and demand.

Regular readers of this space will know mitigating the worst aspects of that imbalance, escaping the spiralling disaster of forever-escalating housing prices, would require commitment and action to return the proportion of public and community housing to what it was before governments started to leave shelter to “the market” in the 1990s, turbo-charged by negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount.

But that’s not happening. The federal government’s public and community housing initiatives will help some individuals and are a big improvement on the Coalition’s lost decade, but they are not enough to make a significant impact on the crisis.

As policy stands, the inequality between housing owners and the rest is set to grow with the best advice for people hoping for shelter security being to pick their parents wisely.

The commentariat is increasingly barking about the role housing problems will play in the next election with concerns increased by every new population growth statistic.

Part of the immediate need to be seen to be doing something is Labor’s belated tightening of the student visa rorting the Coalition had unleashed.

Education is a fine export industry, if done well, not if exploited by fraudulent private operators and universities chasing dollars and ignoring falling standards.

The bind universities are in is another example of second-rate policy coming home to roost – the Law of Unintended Consequences is always working. Because governments did not want to adequately fund tertiary education, providers became dependent on selling enrolments to foreign students without having to provide the necessary infrastructure (housing) to accommodate them – the community overall now paying for that.

The Dutton opposition, staying in its lane of divisiveness and negativity, is happy to blame Labor for migration numbers without offering actual policy itself, let alone explaining which migrants it wants to restrict.

That the Liberal Party, officially allergic to public housing, has only been able to offer “access your super for a deposit” as a solution pretty much sums up its policy vacuity.

If the Liberal policy was attached to a commitment to restore public/community housing to pre-1990 levels and allow use of super to access government-provided housing, as in the Singapore model, it would have some credibility. But it isn’t, it won’t be and it doesn’t.

The suspicion remains that the main reason for the opposition proposing accessing super for housing is the Liberal Party’s hatred of industry super funds and its desire to weaken them.

Dave Sharma, the failed member for Wentworth bumped into the Senate by the Liberal Party, curiously received some passing attention for mentioning housing in his maiden speech as a Senator last week. I don’t know why as his cliches amounted to nothing more than a whinge while stating the obvious and repeating the usual failed mantra of the real estate industry.

“The failure here is overwhelmingly one of supply,” Senator Sharma declared, in the class of discovering the sun rises in the east.

“There are a myriad of reasons for this – very slow and cumbersome planning, approval and land release processes, too much bureaucracy.”

No, Dave, that little collection is not the reason, it’s just what the developer industry constantly spouts against the actual evidence. Regurgitating the lines just illustrates you and your party are clueless and irrelevant when it comes to housing.

Which means the real opposition the government has to deal with on housing remains the Greens, pushing for more public/community/social housing and rental freezes and caps, appealing more to the roughly one-third of Australians renting.

Construction inflation subsiding and weak private building applications make it a more favourable time for governments to directly invest in housing – if they are serious about the problem.