Alan Kohler: Australia is having a family-sized recession – a story in charts

Australia’s household sector is in a long, deep recession, the worst in 40 years.

“Household” is an economist’s word for “family”, so another way to put that statement is that we’re in a family recession, and it’s a big one.

The good thing, politically, about immigration is that the gain is statistical while the pain is anecdotal, and in economics and media, statistics are reality while anecdotes are a buffet – choose one to taste, which means it can be ignored or disputed.

Immigration statistically masked last year’s recession.

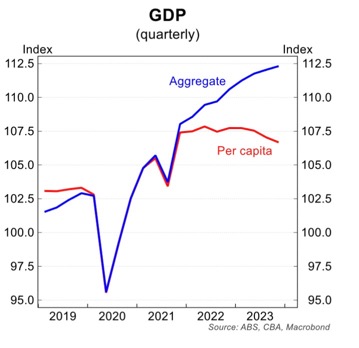

In 2023 total national gross domestic product (GDP), or output, rose by 1.5 per cent in four successive quarterly bumps of 0.6, 0.5, 0.3 and 0.2 per cent.

However per capita GDP – dividing GDP by population – fell 1 per cent in 2023, in four successive quarterly declines. In the March quarter it fell by just one dollar, from $22,821 to $22,820, but then the falls in the other three quarters of 2023 were -0.3, -0.5 and -0.3 per cent.

That is still four consecutive declines – something that hasn’t happened since the 1982 recession. But in 1982, and 1991, per capita GDP fell because total GDP fell and per capita GDP went with it. They were recessions. But this time it isn’t, at least not officially.

Throughout 2023, economic growth was entirely due to population growth, specifically immigration.

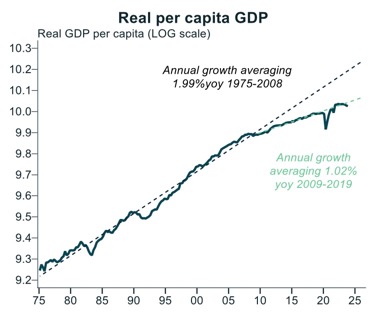

What’s more, the growth rate of GDP per capita (and GDP itself) halved during the GFC, from 2 per cent to 1 per cent a year and never recovered.

Source: IFM Investors

And then in the pandemic, per capita GDP departed from aggregate GDP.

But while GDP might be beloved by economists and statisticians and give us the official definition of recession, it’s irrelevant to families.

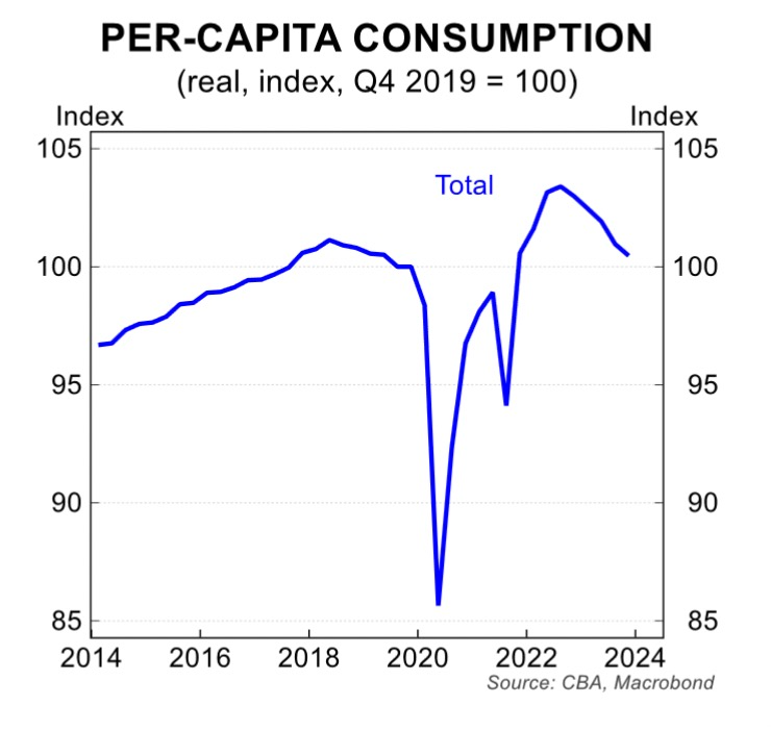

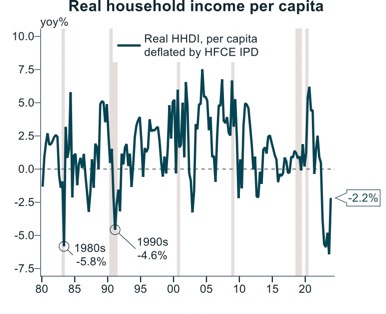

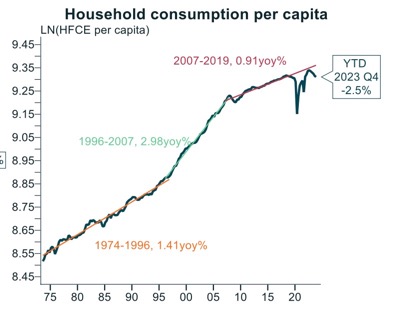

What matters to them are income and consumption – that is, how much you get in the hand and what you can buy with it, and in per capita terms, not distorted by immigration. Here’s what those two things look like:

Source: IFM Investors

Source: IFM Investors

So the decline in each Australian family’s income and consumption in 2023, on average, was more than twice as great as the decline in per capita GDP.

At one point the decline in real per capita income was more than 5 per cent – roughly the same as the recessions of 1982 and 1991.

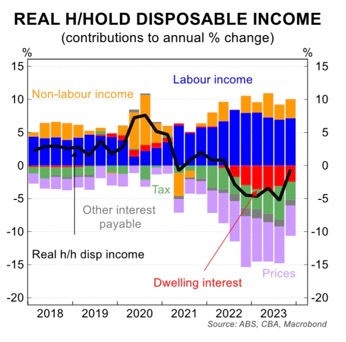

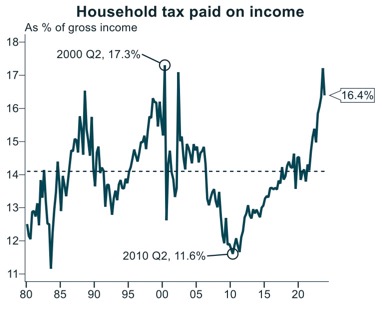

In the statistical aggregates it was masked by immigration, but what caused household incomes to fall? Tax.

Source: IFM Investors

That’s been exacerbated by rising interest rates, which have caused a larger fall in disposable income – that is, income after paying the mortgage, tax and essentials.

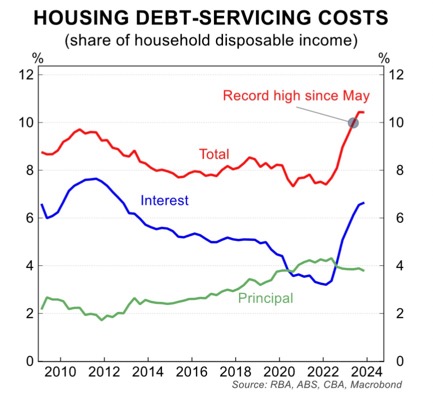

Interest paid on housing debt is up by 39.4 per cent in 2023, and by a massive 162 per cent since the pandemic’s lows. Very low fixed-rate mortgages will continue to switch to variable rate during 2024, which will mean interest paid continues to grow rapidly until the RBA cuts the cash rate.

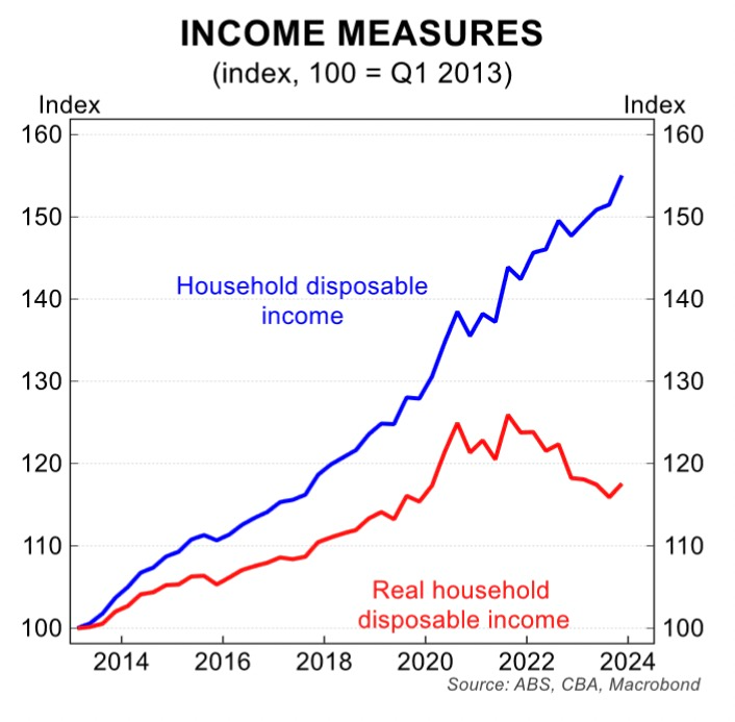

And then what families get for their disposable income is being chewed up by inflation, which can be clearly seen in this chart comparing nominal (before inflation) and real (after inflation) household disposable income.

As a result, real per capita consumption has fallen 2.4 per cent over 2023, which is the sort of thing you only see in a recession or with a major external shock, such as a pandemic.

All of this data came out of last week’s national accounts, which were weaker than the RBA or anyone else had expected, and led the nation’s economic collective to conclude that interest rates would start being cut from September to prevent a recession.

But Australia is already in a recession – a family recession.

The rate cuts are arguably already too late.

Alan Kohler writes twice a week for The New Daily. He is finance presenter on the ABC News and also writes for Intelligent Investor