Alan Kohler: The Evergrande collapse is a wake-up call for Australia’s export strategy

After Japan went broke in 1990, Australia turned its export sales efforts towards China, to great effect.

In 1989, exports to China were $765 million; by 1995, they totalled $1.8 billion and by 2005, $12.3 billion. Now China takes 36 per cent of Australia’s exports and this underpins national income and the Australian lifestyle.

The collapse of property developer Evergrande Group this week was a reminder that China may be going the way of Japan in the 1990s, so the question is: Where to next for Australia’s rocks and gas?

The answer is India, or at least that’s what Trade Minister Don Farrell hopes: A month ago Australia’s new trade agreement with India, the Economic Co-operation and Trade Agreement came into force, with Don Farrell brightly touting it as opening the door to an “export bonanza”.

But there’s a long way to go. Right now, Australia exports as much to China per month, as it does to India per year.

Lessons of history

Will China really go the way of Japan?

To quote from Mark Twain: History doesn’t repeat but it often rhymes. China’s experience from here probably won’t be a repeat of what happened to Japan, but it looks like it will rhyme.

The liquidation of Evergrande ordered by a Hong Kong court on Monday won’t be China’s Lehman Brothers and cause a panic and global recession, because it’s not a global bank, but that doesn’t mean China won’t have a recession or at best, low growth.

Evergrande’s end comes two years after the company first defaulted on its debt, so to quote Ernest Hemingway this time, it went bankrupt gradually and then suddenly, and the eventual liquidation this week was not a shock.

But since that default on September 21, 2021, the Shanghai and Hong Kong stockmarkets combined have lost about $US7 trillion in value, falling 35 per cent as a result of the property market collapse that brought Evergrande undone.

This week’s liquidation order merely confirmed what everybody knew, which is that Evergrande is worthless and the liquidators and Chinese regulators will have their work cut out dealing with creditors, local and offshore, while trying to make sure that about a million pre-sold apartments get finished, so that a million deposits aren’t lost, suppliers are paid and there aren’t riots in the street.

Offshore creditors and shareholders will get nothing and Chinese debt is currently selling for as little as 2 cents in the dollar, so there isn’t much optimism that the liquidators will get their hands on a lot of assets.

As it happens that fall in the Shanghai composite share index of 35 per cent in the two years since Evergrande’s first default is the same as the fall in the Japanese Nikkei index in the first two years after the 1990 property crash. The Nikkei then went on to fall 80 per cent by 2003.

Uncertainty reigns

Whether that happens to China, accompanied by years of zero economic growth and a slump in imports from Australia, as happened with Japan, is impossible to know. There are both similarities and differences.

China’s misallocation of capital over the past decade or so has been as egregious as Japan’s was, with colossal sums wasted on housing and infrastructure.

The cause of that is also the same: Too much saving and not enough consumer spending. Like Japan, China directed its excess savings towards investing in export industries, then Xi Jinping came up with the Belt and Road splurge on infrastructure in other countries as well as housing and infrastructure in China, with diminishing returns the more of it they built.

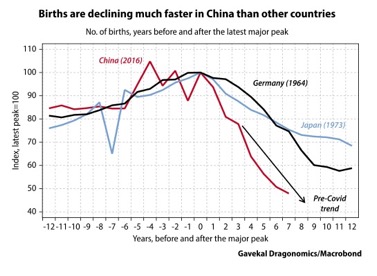

China’s demographic problem is greater than Japan’s was, even though its population is a multiple of Japan’s:

China’s one-child policy between 1979 and 2015 was a disaster, and is directly responsible now for two consecutive years of declining population in 2022 and 2023 – we’re not talking slower population growth, but the actual number of people in China is shrinking. Fewer women of child-bearing age mean fewer births, and fewer people, especially with minimal to zero immigration.

Another similarity is political, although you might not think it. Japan is a democracy, of course, and China an autocracy, but during the 1990s, after the domination of the Liberal Democratic Party ended with the 1993 election, there was a revolving door of prime ministers, coalitions and minority governments.

That meant the place was basically run by faceless technocrats, like China is now, and in Japan they threw out the economic rulebook and ran big budget deficits funded by the Bank of Japan and a policy interest rate of one per cent, that kept Japan one step ahead of deflation.

China managed to stay out of a deflationary spiral in 2023, thanks to Japan-style policy stimulus, but its economy is basically treading water.

Whether Xi Jinping’s government can keep that up is moot, but it’s worth noting that despite all of Japan’s fiscal and monetary stimulus, it’s economic growth still hasn’t sustainably got above 2 per cent.

Major changes needed

The only way to break out of it is for China to become more of a consumer society, rather than an invest-led export and construction one.

To pull that off requires a decent welfare safety net, especially for old age so people don’t feel like they have to save to look after themselves and their families. And that requires not only a lot of money, but a new way of thinking about government.

Perhaps the biggest difference between China and ’90s Japan is the communist government’s incredible success in renewable energy and electric vehicles – which is great, but it’s just more of the same investment-based export-led economic strategy.

Still, China has become the world’s largest exporter of EVs, which is excellent for Australia since they’re made from iron ore, copper, nickel and lithium, although the last two of those have seen prices crash because of an excess of supply.

Coal and gas prices are well down too, as markets begin to anticipate the end of fossil fuels.

But the prices of battery materials should eventually pick up, unlike coal and gas, and in any case, the iron ore price, which is the one that matters most, is doing fine.

During America’s trade war with China when Donald Trump was US president, and our own kerfuffle when Scott Morrison was PM, the Australian government started trying to diversify its exports away from China. That succeeded for a while, but the Chinese share is back above what it was before the pandemic.

It’s an exquisite predicament for any business with one dominant, lucrative customer: It’s great, until it isn’t.

Alan Kohler writes twice a week for The New Daily. He is finance presenter on the ABC News and also writes for Intelligent Investor