Alan Kohler: The RBA is crushing borrowers because of immigration – the government wants them to stop

Photo: AAP/TND

Any doubt that might have existed that another rate hike was coming was removed when, on the afternoon of October 25, Treasurer Jim Chalmers gave a press conference in the Blue Room about the inflation release that came out that day.

It appeared to be a strangely clumsy effort by a normally smart and cautious politician, so we should probably conclude that he meant it.

His message was an internal contradiction: The Reserve Bank is independent and makes up its own mind, but inflation is fine – nothing to see here and, by implication, no need to raise rates.

When asked if it meant interest rates would remain higher for longer, he said: “What we’ve seen today … is consistent with our expectations, it doesn’t materially change the inflation outlook going forward.”

The RBA’s outlook (forecast) for inflation in the September quarter was 0.9 per cent, well below the 1.3 per cent that the ABS had announced at 11.30am on October 25.

The night before, Michele Bullock had given her first speech as RBA governor, a big deal, and said: “The board will not hesitate to raise the cash rate further if there is a material upward revision to the outlook for inflation.”

Chalmers must have known what the RBA’s inflation forecast was when he appeared in the blue room because his Treasury Secretary, Stephen Kennedy, is on the Reserve Bank board.

He also knows that the RBA’s view on inflation, not Treasury’s, is what determines the level of interest rates, but he kept referring to Treasury forecasts, not the RBA’s.

So we can only conclude that he was deliberating telling us there is now a fundamental disagreement between the RBA and Treasury about the outlook for inflation, and distancing himself from the rate hike that he knew was coming on Melbourne Cup Day.

Why do they disagree? Because this government’s main economic policy, like that of the Coalition in 2005-06, is immigration, and it wants the RBA to let it happen without crushing borrowers.

That press conference also provided the new RBA governor with an extra reason to recommend to her board that interest rates had to go up in November – their independence had to be asserted and core inflation was above the staff forecast.

The second thing was actually enough on its own because the Reserve Bank has become an inflation spreadsheet robot, comparing data to forecasts and responding reflexively.

It has forecasts for the quarterly trimmed mean consumer price index which sit in a spreadsheet that goes to the end of 2025 and has inflation below 3 per cent by then.

(The trimmed mean is the measure of core inflation that averages the middle 70 per cent of price moves, leaving out the biggest 15 per cent, and the smallest 15 per cent. The idea is to remove volatile items, whatever they are, in order to discern “core” inflation.)

The December quarter 2022 trimmed mean CPI of 1.7 per cent was announced on January 25. It was well above the forecast in the spreadsheet, so the RBA increased rates on February 8 and March 8, and then paused on April 5 to wait for the March quarter number, due out on April 26.

That turned out to be 1.2 per cent, well down but still above forecast, so they hiked again on May 3 and June 7, and then paused again when they met on July 5 to await the June quarter CPI, due three weeks later on July 26.

The June quarter trimmed mean was 0.9 per cent, below forecast! Ripper! So the RBA paused for the next three meetings, while hanging out for the September number, due to be released on October 25.

It was one of the most consequential data releases from the ABS for years, and it didn’t disappoint in its significance: It was 1.3 per cent, well above the RBA forecast of 0.9 per cent, and a bitter disappointment.

So on November 7, the RBA hiked again. It was a reflex reaction like February and May: Quarterly trimmed mean CPI above forecast; hike rates.

The other thing Jim Chalmers said in that press conference on October 25 is that “the government is doing its bit to take the pressure off inflation”, something he has said many times.

Actually the government is doing the opposite – it’s doing its bit to increase inflation and make life tougher for borrowers, in two ways: through “cost-of-living relief” subsidies and, most of all, through immigration.

The reason the RBA lifts interest rates is to reduce aggregate demand by increasing the debt repayments of borrowers and therefore reduce their demand. The idea is that they cut their demand more than the winners from higher interest rates increase theirs, thus aggregate demand falls.

As ANU economist and former RBA director Warwick McKibbin told the Australian Financial Review this week: “I don’t think the subsidies themselves are doing very much to increase inflation, but they’re certainly not resolving the excess demand problem.”

And how can the Reserve Bank be expected to slow demand when there are half a million more mouths to feed?

Or to be more accurate how can the pain and cutbacks by Australia’s borrowers be expected to slow the demand enough to bring down inflation when 152,200 more people showed up here in the three months to March?

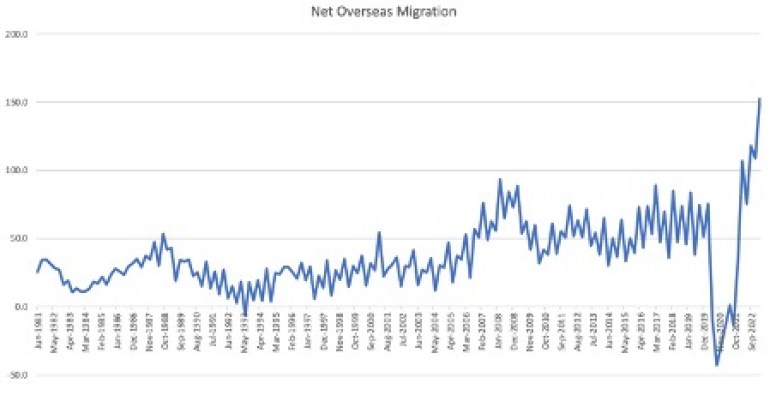

Here is a chart of quarterly net overseas migration going back as far as the Bureau of Statistics has data, which is 1991:

Net overseas migration is running at an annual rate of more than 600,000. The annual growth rate from migration is 2.3 per cent. With the 29,400 births in the March quarter, population growth represented an annual growth rate of 2.8 per cent.

Australia’s population growth has only briefly been above 2.5 per cent per annum four times since Federation: 1910, 1920, 1950 and 1970.

This is causing a massive shock, and changing everything about the economy producing a rebound in house prices, despite the huge increase in interest rates.

It is also leading to stronger than expected top-line economic growth, at the same time as a “per capita recession” – that is, GDP grew by 0.4 per cent in the March and June quarters but on a per head basis it contracted by 0.3 per cent in both.

GDP and aggregate demand would be falling if it wasn’t for 2.8 per cent population growth, and interest rates would be on hold or even getting cut, not increased.

Alan Kohler writes twice a week for The New Daily. He is finance presenter on ABC News and also writes for Intelligent Investor.