Michael Pascoe: No it doesn’t make sense, but have a rate rise

There could be more pain to come in the cost-of-living crisis, Michael Pascoe writes. Photo: TND/Getty

A mere per capita recession isn’t bad enough for the Reserve Bank – it wants living standards to fall further and faster than they have over the past year.

The people at the bottom of the heap haven’t felt enough pain yet.

That was one message spelt out by Governor Michele Bullock in lifting the cash rate by another 25 points.

“While the economy is experiencing a period of below-trend growth, it has been stronger than expected over the first half of the year,” her post-meeting statement says.

Translation: Down economy! Down I say! How dare you not conform with our flawed forecasts?

“Conditions in the labour market have eased, but they remain tight.”

Translation: “More unemployment! We need more unemployment quickly, but we’re not getting it!”

“Housing prices are continuing to rise across the country.”

Translation: You have too much money chasing housing prices higher, which makes you feel richer so you chase housing prices higher! Stop it!

But in the very next sentence:

“High inflation is weighing on people’s real incomes and household consumption growth is weak, as is dwelling investment.”

Translation: Average households are suffering. They’ve been buying less stuff for more than a year now. Nominal household spending is really only up because of the higher price of necessities such as fuel, medical needs and rent. And as for dwelling investment, well, the housing market is stuffed and we don’t know what’s happening there either.

“Inflation in Australia has passed its peak but is still too high and is proving more persistent than expected a few months ago.”

Translation: We don’t know what’s happening, so we’re increasing interest rates again because our forecasts were wrong.

Odd statement

It’s a funny old statement that makes the case for lifting rates and for leaving them stand. Governor Bullock leaves hanging the possibility of another rate rise next month, or not.

Old monetary policy hands warn that the RBA rarely moves just once.

“Interest rate increases are like nuns – they go around in pairs,” Chris Caton once quipped.

Another seasoned observer explains that tendency as being because one move doesn’t make a material difference. Either this one is unnecessary or there’s more to come.

Being in the minority camp myself of thinking this rise was unnecessary, I’m left to wonder if the RBA felt some pressure to meet the market’s expectations, talked into it by the overblown reaction to its own talking.

What could make a difference to the nuns rule (and nuns no longer necessarily go around in pairs anyway) is that our little RBA has just stepped out of line with its Big Brother – the US Federal Reserve and Big Cousin – the European Central Bank.

It’s not entirely true that the RBA is independent – it has to stay in touch with the Fed’s direction unless there’s a very good reason not to. The Melbourne Cup rate rise would have been easier for the RBA if Fed and ECB had just raised at their meetings last week – but they didn’t.

That adds to my suspicion about the pressure of market expectations and the RBA being in a bit of a dither about getting its forecasts wrong.

Whatever the reason, what hasn’t been touched on by the bank yet is the reality of returning money to having a real price.

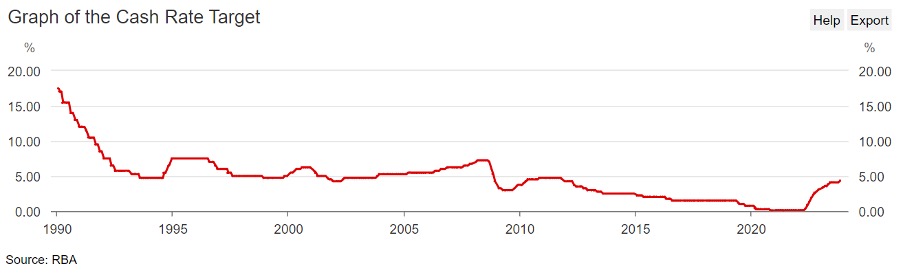

Lifting the cash rate to 4.35 per cent means it is at about its average over the past three decades.

Cheap money gone

The new cash rate is not abnormal or particularly high in the broader sweep of things. What was abnormal was money getting forever cheaper in the lost decade of the teens and then becoming free during the pandemic overreaction.

A constant in much commentary now is speculation about when rates will start falling again from this level. Who says they need to?

And people hoping for rates to fall should be careful what they wish for. Rate cuts now would mean a substantially weaker economy – a real recession, not just a per capita one.

There is very real pain for that minority of people who have hefty borrowings, often people who have never known anything but very cheap money.

Yet in real terms, it is still cheap. The average new home loan is being written about six per cent – only a fraction above the inflation rate that works to magically over time to take care of the cost of assets bought with borrowed funds.

That is of zero comfort to the people who are being sent broke by higher rates, the families who have no money left after paying the mortgage and electricity bills, the people queuing at food banks.

Return to normal

But this is the reality of the world adjusting to money having a price again, of returning to normal.

In one of those tone-deaf statements that our leading bankers seem prone to make, Westpac CEO Peter King on Monday told the Australian Financial Review that borrowers “could accommodate” higher interest rates if warranted.

“They could withstand a few,” the man on a multimillion-dollar salary said after reporting Westpac boosted profit 26 per cent to $7.2 billion.

“I’m not saying it won’t be painless. It will hurt consumer spending and probably affect business more than what we are seeing. But I think that the mortgage customer has been very resilient to date.”

I suspect he meant that his bank didn’t have too bad an exposure to the borrowers who can’t “withstand a few”, that the bank’s profits wouldn’t suffer pain.

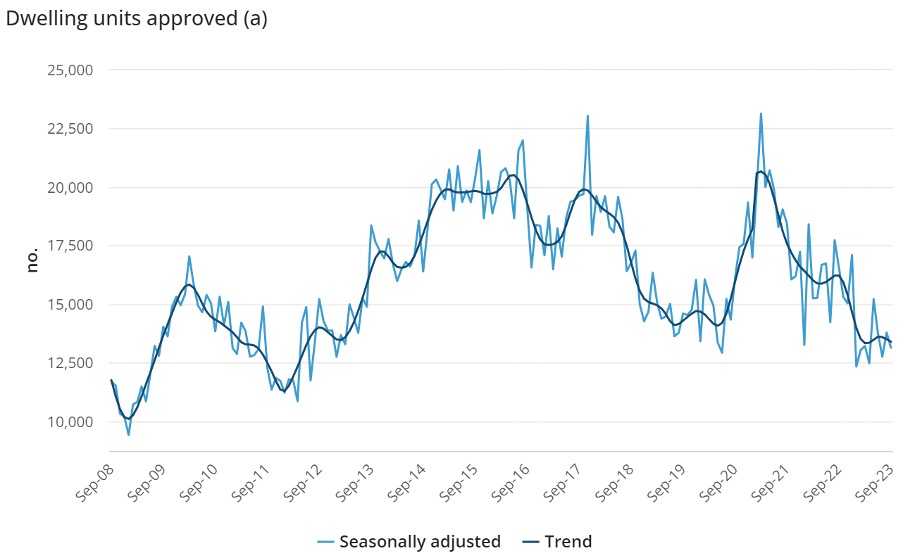

There is no better demonstration of the policy bind the RBA is in than Ms Bullock’s two mentions of housing: On one hand prices continuing to rise, on the other dwelling investment is weak.

There was understatement in both those phrases. Prices are back in record territory while dwelling investment is heading towards the toilet when we are desperately short of more shelter.

Dwelling approvals are down 21 per cent on last year. Approvals over the first nine months of this year are the lowest in 11 years. From these levels, approvals would need to sustainably leap by about 50 per cent to start meeting the government’s “1.2 million homes in five years” fantasy.

Housing conundrum

The RBA’s conundrum is that higher interest rates are supposed to decrease demand for housing and cool prices, but in the process cause fewer dwellings to be built just when it needs more housing to reduce the “wealth effect” of higher prices and rising rents that feed into the CPI which forces the bank to lift interest rates.

No, it doesn’t make sense. The shortage of stock and the resilient demand of strong population growth are not being solved by more expensive mortgages.

As loyal readers know, best weapon for fighting the housing crisis is quite massive direct action by governments building supply themselves, not continuing to outsource their shelter responsibilities to the private sector.

But the RBA doesn’t go there, its pedestrian housing research sticking to the usual real estate industry dogma.

Oh well. It doesn’t make sense, but have an interest rate rise anyway.

And if we fall into a real recession, maybe then governments will invest in public housing as intelligent stimulus investment.