Petrol is holding up inflation – what’s happening to prices and what it means for interest rates

Petrol prices are adding to the interest rate picture in Australia. Photo: TND

Wednesday’s figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics show inflation fell in the September quarter for the third consecutive quarter.

But petrol prices kept it uncomfortably high.

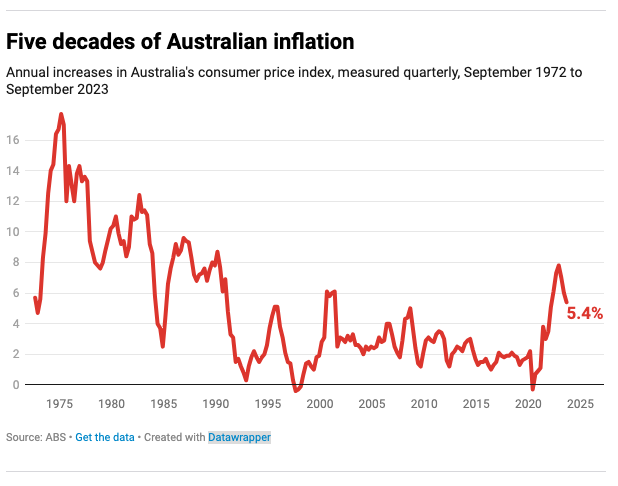

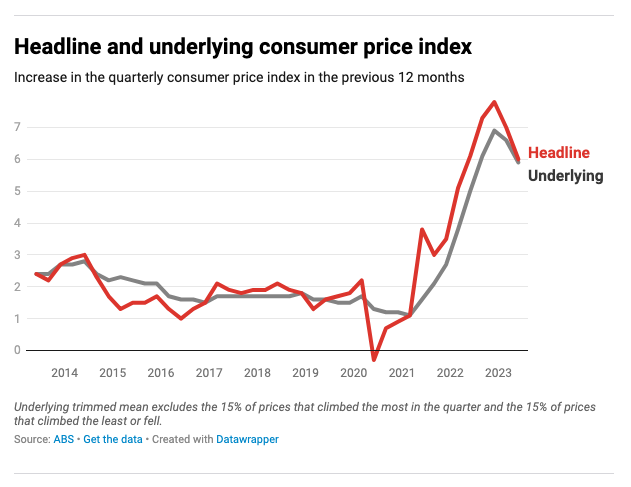

After reaching a 30-year high of 7.8 per cent at the end of 2022, annual inflation as measured by the quarterly index slid to 7 per cent in the March quarter, fell further to 6 per cent in the June quarter and has now slipped to 5.4 per cent in the September quarter. These quarterly results are consistent with the more experimental monthly measure, which also shows annual inflation trending down since December.

These quarterly results are consistent with the more experimental monthly measure, which also shows annual inflation trending down since December.

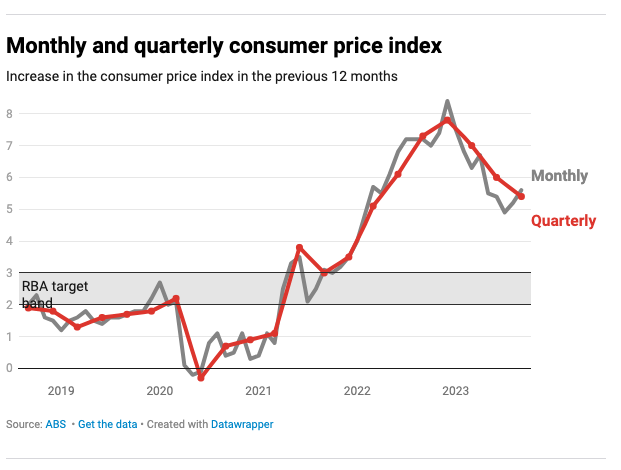

On that measure annual inflation has been broadly falling since December, but has been climbing since it hit a low of 4.9 per cent in July, hitting 5.6 per cent in September largely in response to higher petrol prices and rents.

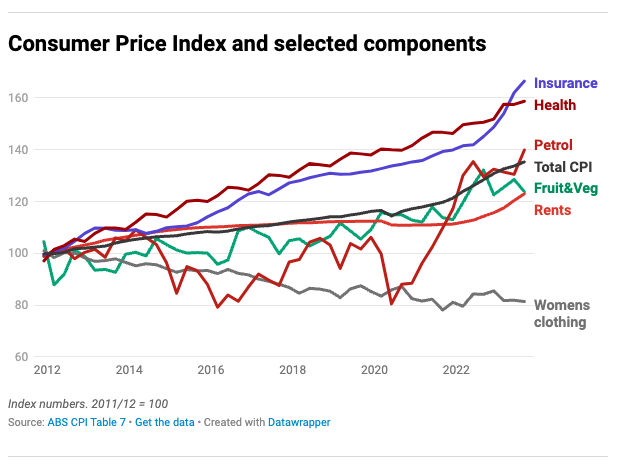

Helping bring down inflation in the September quarter were falls in the price of fruit and vegetables.

The bureau said an unusually warm winter improved yields for salad vegetables such as tomatoes, capsicums and lettuce, and increased the supply of berries.

But pushing it up were increases in the price of insurance (14.7 per cent over the year to September), health care (5.4 per cent) and petrol (7.9 per cent).

Holding inflation back were three budget measures that Treasurer Jim Chalmers said had a combined effect of knocking 0.5 percentage points off inflation:

- Measured electricity prices increased 4.2 per cent in the September quarter. The bureau said without the rebates announced in the budget, the increase would have been 18.6 per cent

- Measured childcare prices fell 13.2 per cent in the quarter. The bureau said without the subsidies introduced in July they would have climbed 6.7 per cent

- Measured rent increased 2.2 per cent in the quarter. The bureau said without the increase in rent assistance announced in the May budget the increase would have been 2.5 per cent.

To get a better idea of what would be happening were it not for unusual and outsized moves, the bureau calculates what it calls a trimmed mean measure of “underlying inflation”.

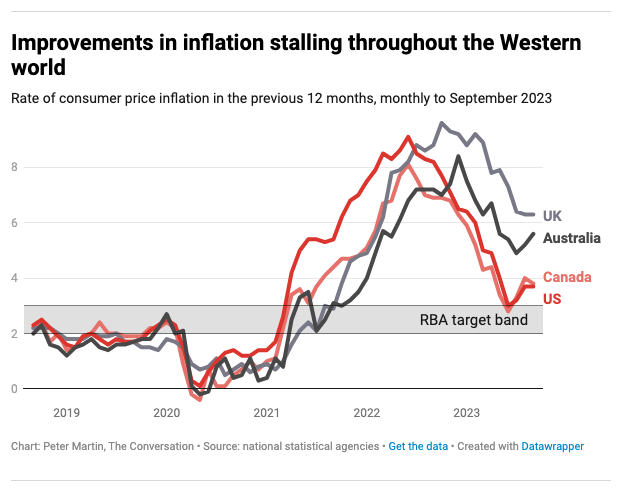

This excludes the 15 per cent of prices that climbed most in the quarter (notably petrol) and the 15 per cent of prices that climbed least or fell. Watched closely by the Reserve Bank, it also shows inflation falling, and down to 5.2 per cent. The fall in Australia’s inflation since 2022 is in line with falls in other Western nations including the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom.

The fall in Australia’s inflation since 2022 is in line with falls in other Western nations including the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom.

Each has been brought about by an easing of supply bottlenecks and slowing economic activity in response to higher interest rates, and each has recently stalled in response to higher oil prices.

(In one nation not graphed – China – there has been almost no increase in prices over the past year, resulting in an inflation rate of near zero.)

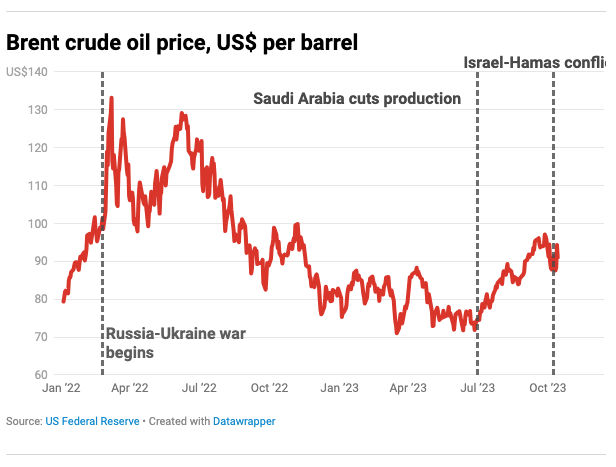

Global oil prices climbed sharply in July after Saudi Arabia and Russia decided to cut production, a year and a half after Russia invaded Ukraine, pushing up oil prices in February 2022.

Global oil prices climbed sharply in July after Saudi Arabia and Russia decided to cut production, a year and a half after Russia invaded Ukraine, pushing up oil prices in February 2022.

In the words of the new Reserve Bank governor Michele Bullock, the world keeps getting hit with “shock after shock after shock”.

What happens from here on in Australia will depend not only on the global oil price, which is expressed in US dollars, but also on the US-Australian dollar exchange rate which has fallen 6 per cent since July, pushing up the price of petrol in Australian dollars.

What happens from here on in Australia will depend not only on the global oil price, which is expressed in US dollars, but also on the US-Australian dollar exchange rate which has fallen 6 per cent since July, pushing up the price of petrol in Australian dollars.

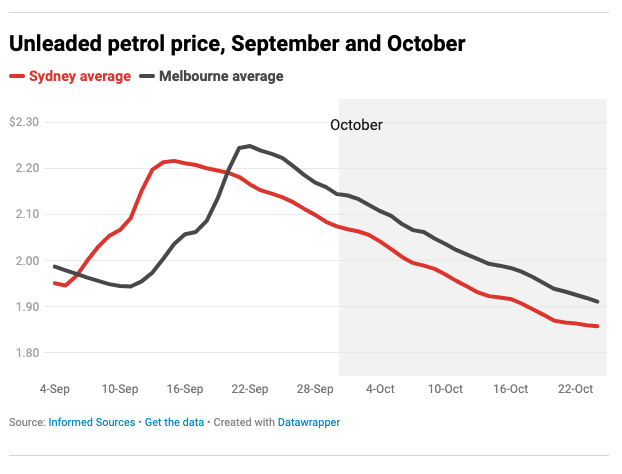

The good news, so far, is that since the end of September (since the period covered by the inflation figures released on Wednesday) the price of petrol has eased.

Where they go from here will largely depend on whether the Israel-Gaza conflict spreads to countries that produce oil.

What does it mean for rates?

Petrol prices aside, inflationary pressures appear to be easing in Australia.

The interest rate increases engineered by the Reserve Bank have slowed spending and have yet to have their full impact.

Although the decade-long decline in unemployment appears to have halted there is no sign of a wages breakout.

In the minutes of its October board meeting, the Reserve Bank indicated it would be examining Wednesday’s inflation numbers closely when it meets on Melbourne Cup Day, November 7, warning it had:

A low tolerance for a slower return of inflation to target than currently expected.

In her first speech as governor this week, Michele Bullock reiterated that the board would “not hesitate to raise the cash rate further” if there was a material upward revision to the outlook for inflation.

On Wednesday, Treasurer Jim Chalmers said the view of his department was that the outlook for inflation had not materially changed.

The RBA will release its revised forecasts on November 10. The last lot, in August, had inflation dropping from 6 per cent in June to a little over 4 per cent in December.

Although Wednesday’s result of 5.4 per cent is a little bit above this trajectory, the underlying measure, 5.2 per cent, is almost on track.

This means while it may make the board members even more anxious, Wednesday’s inflation figure probably hasn’t made another interest rate rise more likely.

Of course, what the board does is up to it. It will decide in a fortnight.![]()

John Hawkins, senior lecturer, Canberra School of Politics, Economics and Society, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.