New book, Fallen, reveals altar boy’s unpleasant George Pell association

Gerald Ridsdale is regarded as the Australian Catholic Church's worst paedophile. Photo: AAP

• Cardinal George Pell was released from prison on April 7, 2020 after the High Court quashed his five convictions for child sexual abuse.

Investigative journalist and writer Lucie Morris-Marr covered the entire Cardinal George Pell abuse case for The New Daily.

Her book, Fallen – The inside story of the secret trial and conviction of Cardinal George Pell, will be published by Allen & Unwin on Tuesday.

During her research for Fallen, Ms Marr uncovered a new victim who has just been awarded redress compensation for a disturbing incident involving Pell and convicted pedophile priest Gerald Ridsdale.

Pell, whose legal team is expected to lodge an appeal with the High Court in coming days against his shock guilty conviction for abusing two choirboys, is being held at Melbourne Assessment Prison after he was sentenced earlier this year.

The New Daily understands he might soon be moved to Hopkins Correction Centre near Ararat, where Ridsdale is also incarcerated for his multiple crimes.

In this exclusive extract, Ms Marr reveals the sinister behaviour of Pell and Ridsdale while at a church in Swan Hill, Victoria.

Extract from Chapter 3 Silencing the lambs

Following his ordination, Pell went on to complete a doctorate in church history at Oxford University. While studying, he also served as a chaplain to Catholic students at Eton College. The future must have looked like a glittering and unhindered road map to the top.

Ms Marr’s book, Fallen, is released on September 17. Photo: Allen and Unwin

Over the next decade, his career would flourish but he would be living and working in an area of Victoria that was soiled by malevolent clergymen systematically carrying out the most vile acts imaginable, using their positions of power and responsibility to sexually abuse local children.

Much later, the country would learn that the Catholic stronghold of Ballarat was in fact one of the epicentres of clergy abuse in Australia. It played host to manipulative, hypocritical priests and Christian Brothers teachers, in particular, who were grooming altar boys, school children, choirboys, orphans and the children of trusting parishioners.

The sheer scale of the criminality and abuse would cause a legacy of self-harm, suicide and despair among the victims and their families that still reverberates today.

It was clericalism at its most loathsome, where loneliness, power and opportunity for sexual gratification collided with a pathological disregard for the pain and terror inflicted.

It would emerge later that nuns too could be sexually abusive and brutally violent to children in their care.

Pell returned home to Ballarat in 1971. With his long, wavy mahogany locks, he looked like the fifth Beatle. He still had an Australian accent, but one rounded off with an upper-class note, thanks to his time at Oxford.

‘He was literally hero worshipped,’ a female family friend remembers. ‘I was 12 years younger than him and I just remember my grandparents talking about him and praising him non-stop. We were all Catholics in Ballarat back then and George was viewed as God’s gift.’

Pell soon found himself working closely with his old family friend, the reigning king of the clergy abusers, Gerald Ridsdale, who’d been attacking children almost as soon as he left the seminary.

For his first posting, Pell replaced Ridsdale as assistant priest at St Mary of the Assumption, a small Catholic parish church at Swan Hill, in north-west Victoria.

Some parishioners believe their roles overlapped and that Ridsdale would visit Swan Hill frequently enough to become a regular noted presence. They remember seeing the pair together taking services and marshalling the choir and altar boys.

Ridsdale later admitted he had abused boys in the area, with one altar boy claiming many years later he’d been attacked on several occasions by the prolific pedophile.

One man who has troubling memories regarding this part of Pell’s early career is a former Swan Hill altar boy called Stephen Scala.

He has never revealed his haunting story to anyone until now. George Pell, he said, had a detrimental impact on his life.

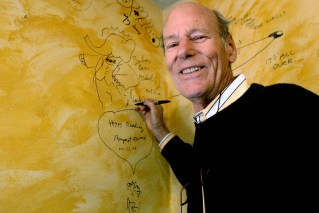

Mr Scala was 10 years old when he came in contact with Pell. Photo: Stephen Scala

He describes Pell and Ridsdale’s friendship as a ‘double act’, even though officially Ridsdale had left Swan Hill and was based at St Alipius Church in Ballarat East.

Special altar boys

Scala, then about 10 years old, first approached Pell in the church one day after a service, telling him how he ‘dreamed of becoming a priest’.

‘I clearly remember telling him I wanted to be a priest,’ he recalled. ‘He said in response, “You have to be one of the special altar boys if you want to become a priest and we think you will be”.’

Scala felt ‘very uncomfortable’ at the direction of the conversation. ‘Pell then said to me: “We will invite you to come to the presbytery to have dinner one night and if things go well you will be able to sleep over”.

‘There was no need for me to sleep in the presbytery, I could get on my push bike and go home. We all could.’

It may well have been an innocent enough suggestion from Pell, but it was enough to make Scala feel awkward. After the conversation, Scala recalls Pell sending him to an upstairs room in the church to speak to Ridsdale.

‘Ridsdale sat opposite me and touched me high up on the inner thigh, and moved his chair towards me. He was telling me something about joining the special altar boys and that he wanted to get to know me better,’ Scala remembers.

Scala, now an author living at Sea Lake, Victoria, felt emotionally out of his depth during the disturbing conversations with Pell and Ridsdale and found himself laughing nervously and loudly when he was in close proximity to Pell.

‘It was like a reaction I couldn’t control,’ he explains. ‘I was only young, but my instinct was Pell was quite monstrous and frightening.’

The laughter did not sit well with Pell, Scala revealed.

‘He sacked me and told me I wasn’t good, almost suggesting I was evil.’

Painful fallout

While it was a relief for Scala to leave the church, he would suffer a painful fallout with his highly committed Catholic mother.

‘Our relationship came under great strain,’ he said. ‘I got the impression Pell had spoken badly to her about me and that was devastating for me. Like many people my mother looked up to Pell and he was God’s representative on Earth, he could do no wrong.’

Pell is expected to appeal against his sentence to the High Court this week. Photo: AAP

After sharing his story, Scala approached the Sano Task Force for guidance. In June 2019 he was offered compensation under the National Redress Scheme, along with an offer of counselling and an apology from St Mary’s.

An official letter from the scheme recognised that the abuse he experienced as a child ‘was wrong and should never have happened’.

Soon Pell would be living in the now-infamous presbytery at St Alipius in Ballarat East, where wrongdoing was a part of the daily routine.

Pell was the Episcopal Vicar for Education in the diocese, and in 1973 he shared the pretty, single-level, red-brick house with Ridsdale, who worked as the priest at St Alipius Church next door.

Living with Ridsdale during Ballarat’s dark era of clergy abuse and later being part of a committee that decided Ridsdale’s new postings would haunt Pell.

It formed a large part of the thunderous cloud of scandal that would follow him for his entire career.