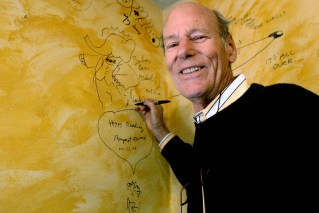

Bob Brown on passion, politics and prison

When Strawberry the cow lifted her tail and shat all over me, her owner explained: “Poor Strawberry, she’s nervous!’. As the newly-arrived local GP, I had been called to attend her wounded leg. It took a dip in the Liffey River to fully recover from this unusual house-call.

“St Paul himself insisted that homosexuals be put to death and, for this eleven year old boy, that meant me.”

That was in 1974 and I was settling into ‘Oura Oura’, the little farmhouse under the towering turrets of Taytitikitheeker mountain in northern Tasmania. I also met up with the young Tasmanians who had formed the world’s first Greens Party during the furore over the destruction of Lake Pedder.

• GREG COMBET: The sometimes ‘peculiar’ Mr Rudd

• Buzz books for 2014 that you can’t miss

My first tilt at politics, on the Greens’ Senate ticket in 1975, was rewarded with 199 of the state’s 247,000 votes. In 1976, I took up a challenge to raft the wild Franklin River and found myself, paddles flailing, in the rapids of environmental politics. I ‘came out’ as gay and was publicly flayed but nevertheless, after a spell in Risdon Prison during the Franklin dam blockade, won a seat in the Tasmanian House of Assembly. That led in turn to a seat in the Senate in 1996.

When I retired from parliamentary politics in 2012 there were a number of requests for an autobiography. I wasn’t keen. However Hardie Grant’s Pam Brewster caught up with me at the 2012 Byron Bay Writers’ Festival and suggested a book of anecdotes. I read Tim Costello’s collection called Hope, liked it, and agreed. Hence Optimism: Reflections on a Life of Action is a book of 53 stories.

When I retired from parliamentary politics in 2012 there were a number of requests for an autobiography. I wasn’t keen. However Hardie Grant’s Pam Brewster caught up with me at the 2012 Byron Bay Writers’ Festival and suggested a book of anecdotes. I read Tim Costello’s collection called Hope, liked it, and agreed. Hence Optimism: Reflections on a Life of Action is a book of 53 stories.

I enjoyed beginning with tales from my childhood, like the one about Constable Brown, my father, locking me up in the Trunkey Creek police cell for not eating my mother’s spinach.

Tasmania’s beautiful Liffey valley figures, as it should, as the anchor which halted the drift of my early adult existence.

My passion for having seven billion human beings use our collective nous to keep this unique planet liveable long into the future inevitably threads its way through the text.

Optimism or pessimism, take your pick. Favouring the former, is there any more inspiring point to our existence than to ensure the planet’s biosphere is passed on in good health so that life – not least human intelligence – can prosper far into the future?

However, unlike the current prime minister, John Howard was personally courteous.

Yet I found it difficult to prosper in the 1950s. The sign over the stage at St Paul’s Presbyterian Sunday School in Armidale said “God is Love”. But St Paul himself insisted that homosexuals be put to death and, for this eleven year old boy, that meant me. While the death penalty for male homosexuals had been abolished in Australia – most states had legislated a penalty of 20 years in jail instead – my own homosexuality was emerging and I was imploding. It would be years before I could see what a mistaken wowser St Paul was and why I should go with my own God-given sexuality no matter what the laws were.

This was good experience with which to later confront the self-proclaimed ‘saints’ of the Exclusive Brethren sect who, as well as being acquainted with Prime Minister Howard, were wreaking havoc on the lives of those Australians they excommunicated. My encounter with these men forms one of the anecdotes in Optimism.

I requested an index and was not surprised to find Howard got most mentions – he was Prime Minister for most of my Senate years. Besides our differences on the Exclusive Brethren, I took issue with Howard over sending Australian troops to Iraq and Afghanistan, his obsequiousness to President George W Bush, and his personal death sentence on the ancient forests in Tasmania which he had never seen.

I requested an index and was not surprised to find Howard got most mentions – he was Prime Minister for most of my Senate years. Besides our differences on the Exclusive Brethren, I took issue with Howard over sending Australian troops to Iraq and Afghanistan, his obsequiousness to President George W Bush, and his personal death sentence on the ancient forests in Tasmania which he had never seen.

However, unlike the current prime minister, John Howard was personally courteous. Unaware of it, he had also patterned his banning of semi-automatic machine guns, after the 1996 Port Arthur massacre, on legislation which I had unsuccessfully brought before the Tasmanian parliament prior to the massacre and which Christine Milne (who had replaced me as leader of the Greens in the Tasmanian parliament) immediately brought forward.

Optimism draws on remarkable people I have met along the wider way like … Jimi Hendrix whose lifeless body was brought to the hospital where I was working in London in 1970.

Not a few politicians, after delivering a rousing first speech, go sallow and quiet in the turmoil of parliaments and retire to the backbench with wounded ideals, never to be heard of again. As a lone Green in the Tasmanian parliament in 1983, and then the Senate after 1998, I found plenty of good policy options to promote; for example countering both Labor and the Coalition when they voted to legislate a ban on equal marriage and when both ignored the growing public support for death with dignity.

I survived a rash mistake in my formative parliamentary years which would have banned lesbian sex in Tasmania. In Optimism I have returned to that harrowing event and how Joh Bjelke-Petersen saved the day for me.

I was fortunate to have thoughtful and resilient Green companions all along the Senate way like Christine Milne, Drew Hutton, Ben Oquist and Margaret Blakers.

Optimism draws on remarkable people I have met along the wider way like Columbian Greens Senator Ingrid Betancourt who was chained by the neck to a tree for months in the Amazonian jungle, old John (I don’t remember his surname) whose solitary life was buoyed by an impossible love, and Jimi Hendrix whose lifeless body was brought to the hospital where I was working in London in 1970.

Out of parliamentary politics after thirty years like a bird out of the cage…

The book also includes some Earthian philosophy: one person, one vote, one value, one planet. Our planet’s future depends on global democracy (though the Australian Senate has repeatedly voted against it) but instead we have de facto global governance by the unelected rich. This is a pernicious rort and, as Rupert Murdoch warned in a different context, “whatever you do, don’t let the bloody Greens mess it up”.

(While invited, I didn’t make it to Rupert’s 50th birthday bash for The Australian in Sydney earlier this month.)

In 1995 I met up with southern Tasmanian farmer Paul Thomas. My life took on a new zing. Nowadays I love speaking to students about the future and when asked, as I frequently am – ‘why aren’t you depressed?’ – my answer is ‘because of this beautiful planet and Paul’. He is my irreplaceable life companion and I am the happiest I have ever been.

Out of parliamentary politics after thirty years like a bird out of the cage, and with pen in hand, I am enjoying the years left to me on the finest little planet in the Cosmos.

Optimism: Reflections on a Life of Action will be released on August 1 through Hardie Grant.